I was honored to be asked to speak at the Freeman-Hagans reunion last night — the first family reunion I’ve addressed beyond my own. The family is fortunate to have richly documented genealogical knowledge, so I knew I couldn’t just show up and tell the Freemans about the Freemans. As I considered topics, I remembered a passage in Mary Freeman-Ellis’ fantastic The Way It Was in which she vividly described attending services at London’s Primitive Baptist Church. As genealogy is brought to life, so to speak, by an understanding of the contexts of our ancestors’ lives, I decided to talk about the history of the church that was so central to the lives of Eliza Daniels Freeman and several of her children. My thanks to Patricia Freeman for the invitation; to the Lillian Freeman Barbee family for sharing their table with me; and to all who welcomed me so warmly.

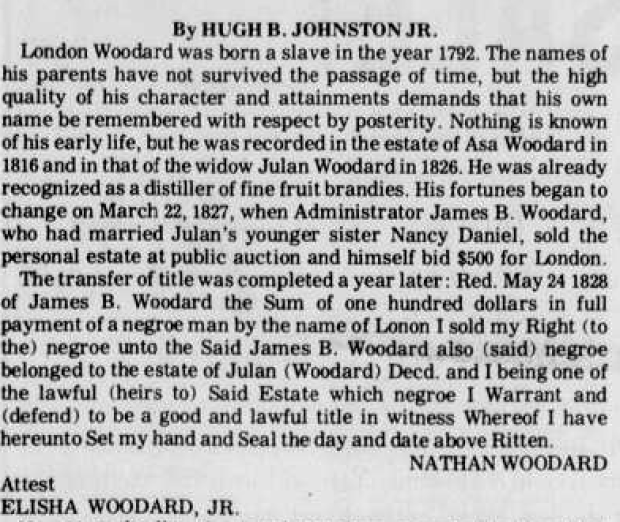

London Church twelve years after it was moved from its original location on Herring Avenue. A hoped-for benefactor had not materialized, and the building was beginning to break down. Wilson Daily Times, 31 March 2004.

Here’s the inspirational excerpt from Mary Freeman-Ellis’ memoir:

“… Aunt Lydia [Freeman Norwood Ricks], Uncle Lovette [Freeman], and Julius [F. Freeman Jr.] were members. Once a year, usually early spring, the church had its annual meeting. People came from near and far. A great deal of time was spent inside the church during the service. This was the annual ‘Big August Meeting,’ I used to hear Aunt Lydia say, lots of preparation occurred during the year to cleanse the heart, soul and the mind in order to be able to receive communion. The church grounds, as they were called, were set up with long wooden tables with benches to sit on. Each table was covered with a sheet then a white table cloth.

“I had never seen so much food any place before. There was fried chicken, roast beef, roast pork, potato salad, slaw and several tin tubs with iced cold lemonade. There were also several kinds of pies and cakes. This was the first time I had ever seen anybody eat only cake and fried chicken together. We tried it and it was good. People ate, greeted each other with big hugs and the preacher did his share of hugging the sisters. London Baptist Church was a primitive church; I never understood that term.

“Although the fellowship of the church grounds was a vital part of this Big August Meeting, what transpired inside was the thing that had us traumatized. For example, the services started with the pastor greeting the congregation. The membership was made up of all blacks and the women far outnumbered the men. The service continued with a long prayer, going into a song led by the pastor. There was no organ or piano. Most of the songs appeared to have anywhere from five to eight verses. I was familiar with the hymn, Amazing Grace, but had never heard it sung the way the Primitive Baptists sang it. The preacher would read off two lines as follows: ‘Amazing Grace, how sweet the sound. It saved a wreck [sic] like me.’ The congregation would follow with these same two lines. The pastor would continue with, ‘I once was lost, but now I’m found, was blind, but now I see.’ This was called ‘lining a hymn.’ The preacher took his text from the Prodigal Son. He had him going places and doing things I had never heard of before. Since we were children, we knew to keep quiet because this was a house of worship and it was good manners to sit quietly. We had also begged Aunt Lydia to take us and we did not want her to know how disappointed we were. There was very little going on for children other than eating when the time came.

“We could not get home fast enough to tell Mother and Dad about our experience, especially how hard those wooden benches were. I wanted the center of attention so I began relating each thing as it happened. Dad momentarily looked up at me for a moment with a sheepish grin on his face. He said, ‘You know you were not forced to go.'”