“The Atlantic Coastline Railroad tracks separated a black and a white world almost. And then there was Hines Street that wasn’t a connector in those days, but just a street. And there was Daniel Hill, where colored people lived. Then there were six houses between Lee and Gold Streets close to the city lot where black people lived. And Mercer Street in Five Points was all black. There were two ice companies near the railroad tracks and one area was called ‘Happy Hills’ where a few blacks lived. ‘Green Hill’ near the other ice company was a white neighborhood. Except for the above-mentioned, I don’t know of one black family that lived beyond the tracks. But I’m not saying there might not have been a few isolated cases. But Daniel Hill was where 99 percent of the black population lived anywhere on the west side of Wilson.” — Roy Taylor, My City, My Home (1991).

The 1930 edition of Hill’s Wilson, N.C., city directory reflects the full flower of segregated Wilson, with street after street east of the railroad occupied entirely by African-American households in patterns still easily recognized today. However, here and there clusters of houses appear at unfamiliar locations, either because the streets themselves have disappeared or because we have lost collective memory of these blocks as black neighborhoods.

Here are a few more:

I’ve been unable to locate this street.

An earlier post explored the small African-American settlement that coalesced around Lee and Pine Streets by the turn of the twentieth century. By 1930, this community had contracted to three small duplexes on Lee Street and half-a-dozen around the corner on Pine.

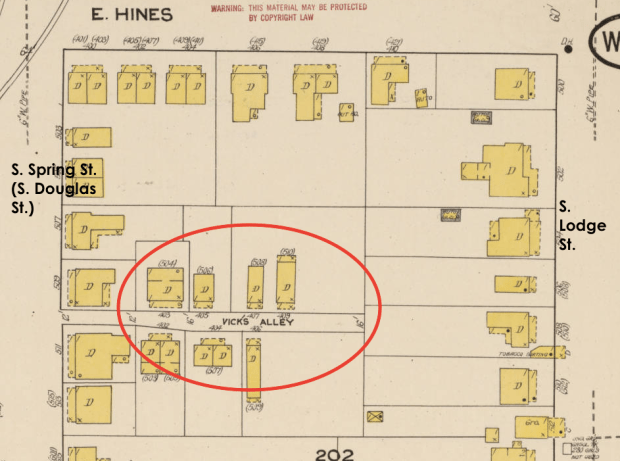

1922 Sanborn fire insurance map, Wilson.

In the 1930 census of Wilson, Wilson County: at 202 Lee Street, paying $16/month rent, Willie Walter, 21, odd jobs laborer; wife Lulu, 15, servant; and roomer Novella Townsend, 25, laundress. Also [in the other half of the duplex], paying $16/month, cook Mamie Nord, 47, and her son Rufus J., 21, odd jobs laborer. At 204 Lee Street, paying $16/month: laundress Lizzie Larry, 49; Maude Lofty, 100; Lizzie’s daughter Anabel Larry, 28, and her sons John H., 12, and M.C., 13. Also, paying $16/month, Jasper Thigpen, 47, transfer truck driver; wife Dora, 33; and daughter Allie, 16.

In the 1930 census of Wilson, Wilson County: at 405 Pine Street, paying $10/month rent, Adele Matthews, 42, laundress, and Sarah McMullen, 23, laundress. Also [in the other half of the duplex], paying $10/month, odd jobs laborer David Sanders, 35, and wife Carry, 44, laundress. At 407 Pine Street, paying $12/month: servant Ella Pulley, 30. Also, paying $12/month, Egarber Barnes, 24, jail attendant, and wife Nanny, 25, laundress. At 409 Pine Street, paying $12/month, practical nurse Lizzie Bullock, 70; and children Ernest, 43, house painter, Obert, 33, hotel cook, and Gertrude, 35, laundress. Also, paying $12/month, truck gardener Charlie Moye, 29, and Edward Williams, 53, farm laborer. At 411 Pine Street, paying $10/month, greenhouse gardener Windsor Ellis, 41; wife Rachel, 34; and children dry goods store janitor Douglas, 20, John H., 10, and Elaine, 5; and lodger Fred Moye, 26, café cook.

In 1930, the east and west ends of South Street were largely home to commercial and industrial outfits. The middle block, however, the 300s, housed in uncomfortably close quarters a stone cuttery, a couple of black families, the black Episcopal church, and a notorious whorehouse. [Update: this was the Little Washington neighborhood.]

In the 1930 census of Wilson, Wilson County: at 304 East South Street, high school janitor Joseph Battle, 80; wife Gertrude, 42; and daughter Clara, 22; and five boarders, Earnest Heath, 24, cook; James Pettiford, 36, barber; Robert McNeal, 23, servant; Essie M. Anderson, 18, servant; and Viola McLean, 24, “sick.” At 306 East South: tobacco factory laborer William Barnes, 28; wife Loretta H., 23; and brother Charles Barnes, 22, servant. At 309 East South, widow Mattie H. Paul, no occupation.

Karl Fleming wrote of “veteran madams” Mallie Paul and Betty Powell, who operated Wilson’s “two twenty-dollar whorehouses,” “sexual emporia [that] had operated for at least thirty years [by the late 1940’s] … situated in similar two-story wood houses near each other just behind the tobacco warehouse district.” Though Fleming curled his lip, Roy Taylor fairly gushed about Paul: “One sight that got my attention, along with everyone else’s in the area when it occurred, was the march of Mallie Paul and her girls from their home on South Street, to women’s stores downtown to purchase clothing, cosmetics, and other necessities. And those women were beautiful! … There would be 10 or 12 of them walking leisurely toward the hotel from Douglas Street, then turning on Nash. …”

Most of Wilson’s tobacco warehouses succumbed to arson in the final decade and a half of the last century, and the 300 block of South Street is entirely industrial.

- Taylor Street and Taylor’s Avenue

Neither exists today.

Neither exists today.

This entire street is gone, cleared for the extension of Hines Street over the railroad tracks (via Carl B. Renfro Bridge) to connect with Nash Street a few blocks west of highway 301 as roughly shown below.

1922 Sanborn fire insurance map, Wilson.

Neither exists today.

Neither exists today.