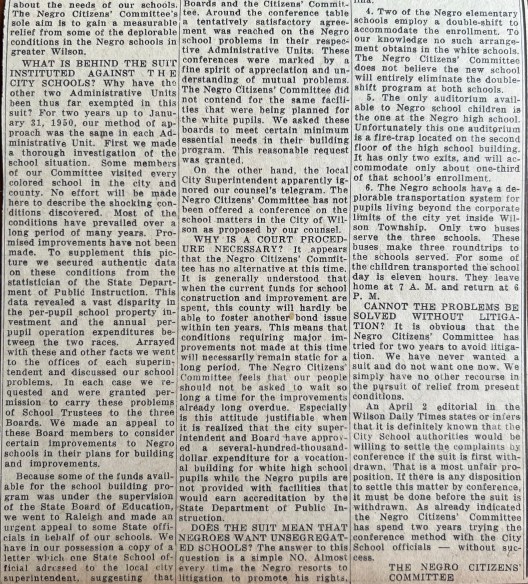

In May 1950, the Negro Citizens’ Committee paid to place an open letter in the Wilson Daily Times explaining the lawsuit it had filed against Wilson City Schools. Takeaways below.

Wilson Daily Times, 6 May 1950.

- The N.C.C. was comprised of African-Americans from every Wilson County township and across the economic spectrum.

- The group neither solicited nor accepted aid from outside the county.

- Members represented 15 churches, eight social organizations, 13 fraternal orders, and nine unions. [Nine unions?? Who were these groups?]

- The group was founded to advocate for improved schools for African-American children in each of Wilson County’s three educational administrative units — Wilson City, Wilson County, and Elm City Public Schools. N.C.C. worked for the success of a bond referendum, believing it would result in improved schools for Black children.

- The committee visited each Black school and discovered “shocking conditions.” After compiling data detailing vast disparities in per-pupil investment and expenditures, N.C.C. appealed to the local school boards and the State to make improvements. None were made.

- In later 1949, after personal appeals went nowhere, N.C.C. retained counsel, who requested meetings with the three boards. N.C.C. was careful to emphasize that it was not seeking the same facilities as white students enjoyed, but “certain minimum essential needs.” Meetings with Wilson County and Elm City went well; Wilson City ignored the request.

- N.C.C. understood that if Wilson City did not budget for improvement of African-American schools in the proceeds from the current bond, there would not be another in the next ten years, which was too long to wait for upkeep already overdue, especially when Wilson City had “approved a several-hundred-thousand-dollar expenditure for a vocational building for white high school pupils while the Negro pupils are not provided with facilities that would earn accreditation ….” [Some of you may remember this vocational building as the Annex across the street from Coon Junior High School, the former all-white high school in Wilson. Despite its cost, it was poorly constructed and in bad shape by time I attended classes there in 1977. It closed in the 1980s, lay vacant and festering for another 20+ years, and was finally demolished about 2006.]

- N.C.C. reassured white citizens that it was not seeking school desegregation. Rather, it sought to end discrimination against Black students in per-capita spending.

- A partial list of inequities in city schools: (a) none of the Black elementary schools had an auditorium, including the new one [Elvie Street School] under construction; (b) because there is no cafeteria in one elementary school [presumably Vick], lunch is prepared in a former janitor’s closet and served to children in their classrooms; (c) the elementary schools do not qualify for accreditation because of their physical plants; (d) two elementary schools [Vick and Sallie Barbour] employed double-shift scheduling to accommodate enrollment; (e) the only auditorium for Black children is at the high school and is a “fire-trap” that can only accommodate about a third of the high school students; (f) the Black schools have a “deplorable transportation system” for children living outside city limits but inside Wilson township [children inside were expected to walk], with only two buses to serve three schools and resulting in eleven-hour days for some children.

- Having tried for two years to avoid litigation, N.C.C. saw no other way. Chiding the Daily Times for suggesting Wilson Schools would settle their complaints if they withdrew their complaint, reminding readers they had already waited two years.