The lands of Revolutionary War veteran Shadrach Dickinson [Dickerson] lay along Contentnea and Black Creeks in what were then Edgecombe and Wayne Counties. His small house is one of the oldest standing in Wilson County. Dickinson died in 1818 leaving a large estate that included numerous enslaved people.

A division of Dickinson’s “lands and negroes” took place in May 1819, and the report of that division shows that his children had received some of their inheritance while their father was alive.

Daughter Elizabeth Stanton received a seven year-old girl named Mourning in 1795; eight year-old Jack and ten year-old Lany in 1819; and, in the general division, Dick and Grace Sen’r.

Daughter Penny Barnes received Hester, 10, and Tamar, 8, in 1814, and Hannah in the general division.

Daughter Susanna Edmundson received Cely, 13, and Lucy, 9, in 1817; Jacob, 7, in 1818; and Anica and Cherry in the division.

Daughter Polley Thomas received Sam, 10, in 1797.

Son James Dickinson received Peter in 1809 and Harry and Clary in 1819.

Daughter Patience Dickinson received Peg and Levi in the general division.

Son William Dickinson received Dick and Grace Junior in the general division.

Daughter Martha Simms received Darkas, 9, in 1793; Arch in 1818; and Warum in the division.

Daughter Sally Jernigan received Jack, 10, and Diner, 6, in 1807; Dury, 6, in 1813; and Smitha in the division.

At least two of Shadrach Dickinson’s children — daughters Elizabeth Dickinson Stanton and Patience Dickinson Turner — migrated to Sumter/Pickens Counties, Alabama, carrying enslaved men and women with them and further sundering family ties strained by Dickinson’s estate distribution. Pickens County proved particularly inhospitable to African-Americans well into the twentieth century, and Sumter County is the poorest county in Alabama. Thousands joined the Great Migration out of the state, and it would not be surprising to find in Chicago and Detroit and Cleveland today descendants of Shadrach Dickinson’s enslaved.

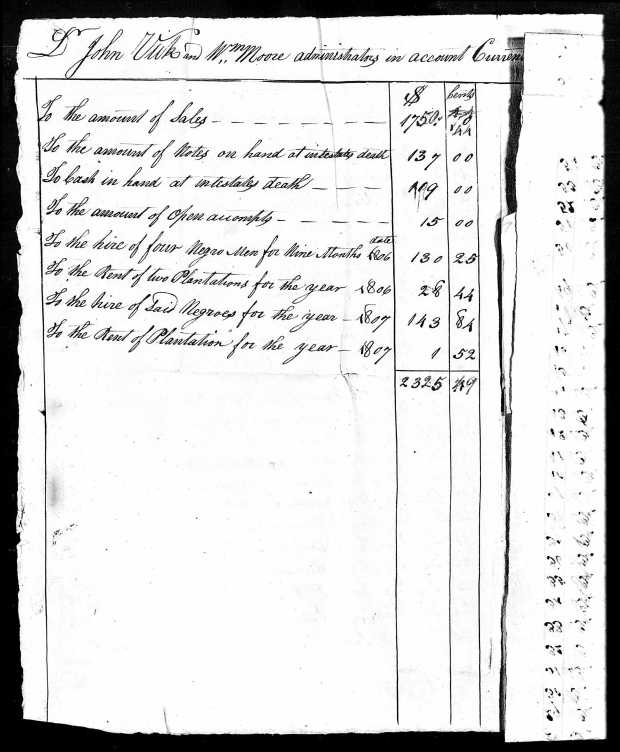

Estate File of Shadrach Dickinson (1819), Edgecombe County, North Carolina Wills and Probate Records, 1665-1998, http://www.ancestry.com.