While director of the University of North Carolina Press, W. T. Couch also worked as a part-time official of the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration, serving as assistant and associate director for North Carolina (1936-1937) and as director for the southern region (1938-1939). The Federal Writers’ Project Papers are housed at U.N.C.’s Southern Historical Collection and include Couch’s correspondence and life histories of about 1,200 individuals collected by F.W.P. members. At least two African-American residents of Wilson, Georgia Crockett Aiken and William Batts, were memorialized in this way.

Folder 324 contains the transcript of the interview with Georgia Crockett Aiken, titled “Women are best.”

The first page is a key to the pseudonyms used in the transcript.

Georgia Aiken is mistakenly described as white. She lived at 120 Pender Street in Wilson. When her interview began, she was in her kitchen directing the work of two children who were cleaning the house. She was born in 1872 into a family of ten children, all of whom were dead except her. [The family had lived in Goldsboro, North Carolina, and Georgia’s brothers included Alexander and James Crockett.]

Georgia Aiken grew up near a school and, because both her parents were wage-earners, was able to attend through the ninth grade. She obtained a teaching certificate and started teaching in 1889 a one-room school “out in the country.” She made $25 a month for teaching seven grades and reminisced on the hardships — and reward — of serving the children of the community.

In 1908, Georgia Aiken arrived in Wilson. She started high school coursework [where? the Colored High School did not open until 1924] and received a big raise when she completed it. She taught for 48 years, all told.

She dated John Aiken for two years before they married. Aiken owned a prosperous livery stable, and the couple saved their money to build a house. When they bought the Pender Street lot, a widow lived with her children in a small house there. [A 1905 plat map shows John Aiken already owned a lot on Pender Street. Was it a different one?] John Aiken died before the house was completed [in 1914] and Georgia Aiken took over the business.

Though worried about finances, Georgia Aiken went ahead with plans to build. The livery business did well until “automobiles came in.” She sold the business at a loss and turned her attention to teaching and caring for her house.

The writer described Aiken’s kitchen in deep detail.

Her “cook stove … finished in blue porcelain” was probably much like this one, found in an on-line ad:

Aiken continued, speaking of training her helper, her standards for housekeeping and food preparation, and her preference for paying cash.

And then: “I might as well say that I voted in the last city elections and have voted ever since woman’s suffrage has come in, and I expect to as long as I can get to the polls. I would like to see some women run for some of the town offices. I think they’re just as capable as the men who set themselves up so high and mighty. I wouldn’t be the least surprised if women didn’t get more and more of the high positions in the near future. …”

And: churches and government are run by rings, and “if you don’t stand in well with these, you don’t stand a chance.”

“I believe the women do more in church work than men.”

Georgia Aiken took in boarders at her home on Pender Street and always tried to make her “guests feel at home.” “When times are good and business is stirring” — likely, she meant during tobacco market season — “I always have my house full.” In slow times, though, it was hard to meet expenses. Taxes were due and though she knew she would make the money to pay them in the fall, she hated to incur fees.

Aiken paid her helper in board and clothes only, though she wished she could pay wages. If she stayed long enough, Aiken would consider leaving her some interest in the property after her death, though her niece in New York might object. She lamented a long delay in repainting the exterior of the house, but had plans to do so.

The writer described the house’s rooms and furnishings, mentioning their wear and age. Aiken indicated her preference for “clean decent folks” as tenants. She had two baths in the house and hot water from the stove for both. She could not afford to install steam heat when the house was being built and rued the dustiness of coal.

“Helping anyone in need is being nice to anyone, and the one that helps me most during the few years that I’ve left in this life is the one I hope to remember with the most of what I leave when I’m called to the life to come.”

A summary:

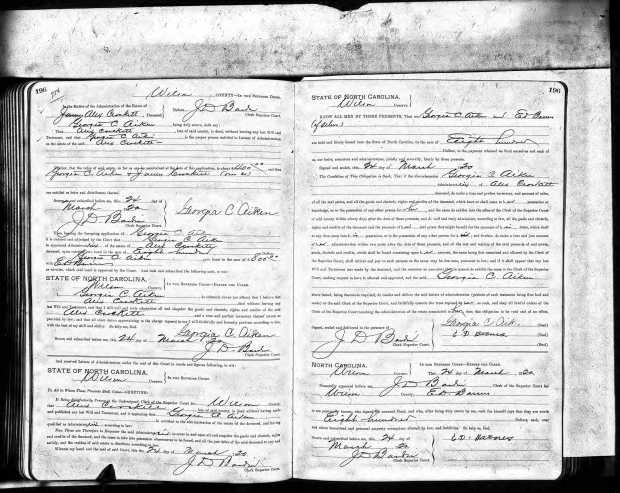

Georgia Crockett Aikens died 17 August 1939 in Wilson, apparently just a few months after giving this interview. Per her death certificate, she was 67 years old, born in Wayne County to William Crockett and Rachel Powell, resided at 120 Pender Street in Wilson, and was married to John Aikens.

“Federal Writers’ Project Papers, 1936-1940, Collection No. 03709.” The Southern Historical Collection, Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.