Wilson Advance, 16 February 1899.

——

Wrote Bainbridge and Ohno in Wilson, North Carolina: Historic Buildings Survey (1980):

“Finch’s Mill Road was developed in the 1920’s on the former site of a shantytown.”

The “shantytown,” of course, was an African-American community. Until the 1920s, Finch’s Mill, like nearby Grabneck, was a black westside neighborhood.

“A natural extension of Residence Park, lying between that neighborhood and the main road to Raleigh (Rt. 264), Finch’s Mill Road, as it name suggests, once led to Finch’s Mill, outside of Wilson. A major change in the roadway in the 1920’s and then again in the 1970’s has changed this neighborhood. In the 1920’s Finch’s Mill Road became a less traveled way and it linked the older residential neighborhoods to the fashionable neighborhood which was to grow in the 1930;s along the Raleigh Road axis beyond Recreation Park. Finch’s Mill Road sill branches this gap between the old and the new neighborhoods. The character of the neighborhood is mainly residential, although the Recreation Park creates a large public open space. A few houses were built here in the 1920’s, but the bulk of the growth of the neighborhood took place after 1930, although few houses are being constructed in the 1970’s.”

Here is Finch’s Mill Road as depicted in the 1922 Sanborn fire insurance map, branching west off the northern end of Kenan Street and heading out toward Nash County. It is lined with tiny duplexes, likely no more than one or two rooms per side. (Finch’s Mill Road is now Sunset Road. South Bynum roughly follows the course of today’s Raleigh Road; the little spur is Cozart Road; and Sunset Drive is now Sunset Crescent.)

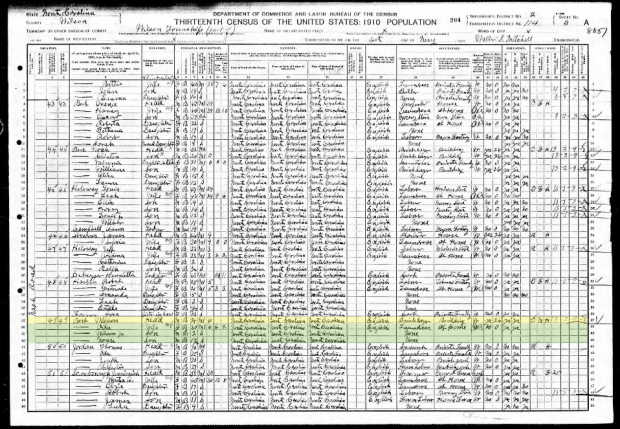

In the 1910 census of Wilson township, Wilson County, 29 households appear on Finch Mill Road, every single one of them African-American.

Excerpt from 1910 census of E.D. 114, Wilson township, Wilson County.

Wilson Daily Times, 22 October 1918.

In 1920, the census taker recorded 23 households on Finch’s Mill, mostly African-American, but with a sizable white minority. All were farmers, and none of the black heads of household owned their land. Soon, however, there would be no farmers of any kind at the end of the road nearest town.

In the mid 1920s, a large swath of the neighborhood, now known as Westover, was subdivided into “high-class residential” lots on Kenan and Bynum Streets, Sunset Road and Sunset Crescent, and offered for sale at auction:

Wilson Mirror, 16 December 1924.

Wilson Mirror, 17 December 1924.

By 1930, the old neighborhood was gone. Hill’s Wilson, N.C., city directory for that year lists only four occupied households on “Finch’s Road” and only one by an African-American family, the Reeds at #630. It’s not entirely clear what thoroughfare was considered Finch’s at that point, as the section of Finch’s Mill off Kenan Street had been rechristened Sunset Road and was home to Wilson’s white elite. The 1930 census lists cotton merchant Willie T. Lamm in a $25,000 house on “Westover.” Next door, in what may have been the last of the little duplexes shown on the 1922 Sanborn map, this household: Louisiana-born farmer Zion Read, 56, his North Carolina-born wife Lara, 25, and children Zoreana, 8, Hesicae, 12, William, 4, and Walter E., 0, in one half, and farm helper Jack Dixon, 25, wife Hattie, 24, their children John H., 3, and Susie M., 0, and a roomer Fes Scarboro, 45, in the other. Each family paid $6/month rent. Nearby, wholesale distributor John J. Lane was listed in a $15,000 house at 1015 Sunset Drive.

This Google Maps image shows today’s short stretch of Sunset Road, formerly Finch’s Mill Road, between Kenan Street and its dead-end at Recreation Park Community Center. The old road would have skirted the swimming pool and continued west across Hominy Swamp toward Finch’s Mill, five miles away near what is now the intersection of Raleigh Road/U.S. 264 and Interstate 95.

——

- Windsor Darden — in the 1910 census of Wilson township, Wilson County: Winsor Dardin, 45; wife Mattie, 35; and children George, 22, Jesse, 16, Willie, 14, Winsor, 12, Charlie, 10, Olivia, 7, Annie M., Leroy, 3, and Mattie, 9 months.

- Luther, Henry and Lottie Harris

Wilson Daily Times, 15 November 1910.