Today marks the 35th anniversary of the passing of Robert D. Haskins, the named plaintiff in a landmark 1982 civil rights lawsuit filed against Wilson County over its at-large system for electing county commissioner.

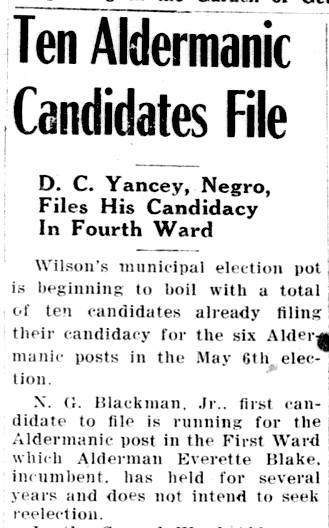

Wilson Daily Times, 31 October 1986.

Attorneys G.K. Butterfield Jr. (now a U.S. Congressman) and Milton “Toby” Fitch Jr. (now a North Carolina State Senator) with Robert D. Haskins. In the early 1980s, on behalf of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, photographer Jim Peppler documented Black Wilson County citizens’ efforts to secure representation on the county’s Board of County Commissioners. The series of photographs are housed at Alabama Department of Archives and History.

——

In the 1920 census of Wilson, Wilson County: Robert Haskins, 37, insurance agent; wife Gertrude, 28; and children Mandy, 14; Elizabeth, 12; Estelle, 10; Robert, 7; Lossie, 5; Laurence, 4, and Thomas, 11.

In the 1930 census of Wilson, Wilson County: Robert Haskins, 44, insurance agent; wife Gertrude, 39; and children Mandy, 22, private family cook; Elizabeth, 20; Estell, 18; Robert, 17; Lossie, 14; Larence, 12, and Tommie, 11.

In the 1940 census of Wilson, Wilson County: Robert Haskins, 55, drug company salesman; wife Gertrude, 48; and children Mandy, 36; Elizabeth, 33, cook; Estelle, 29, beauty shop cleaner; Robert D. Jr., 29, hotel kitchen worker; Lossie, 24, N.Y.A. stenographer; and Thomas, 20, barbershop shoeblack; plus granddaughter Delores Haskins, 15, and lodger Henry Whitehead, 21.

In 1940, Robert Douglas Haskins registered for the World War II draft in Wilson County. Per his registration card, he was born 1 June 1913 in Wilson; lived at 1300 Atlantic Street, Wilson; his contact was father Robert Haskins; and he worked for Robert Haskins as a salesman.

Hat tip to LaMonique Hamilton for the link to these photos.