Alfred Dew signed an X to his will on 22 June 1910, witnessed by Samuel H. Vick and Elijah L. Reid. (Reid was a close neighbor on Viola Street; Vick lived a block away on East Green Street.) Dew left his wife Laura Dew a life estate in all his property, with a remainder in son R.D. Dew. Sons Jack Dew and Needham Dew were to receive ten dollars each and daughter Martha Alston, sixty dollars.

——

On 11 August 1866, Alfred Dew and Susan Dew registered their five-year cohabitation with a Wilson County justice of the peace.

In the 1870 census of Wilson township, Wilson County: Alford Due, 26; wife Susan, 23; and children Jack, 6, Redick, 4, and “no name,” 1 month; plus Oliver Due, 48, Amos Barnes, 23, and Anna Due, 19.

In the 1880 census of Wilson township, Wilson County: farmer Alford Dew, 39; wife Louiza, 35; mother Olivia, 60, widow; and children Jackson, 18, Redick, 16, and George, 15, Needham, 12, and Martha, 10; and niece Hatta, 4. [George was likely George W. White, Louisa’s son from prior relationship.]

On 13 March 1889, Jackson Dew, 25, son of Alfred Dew and Susan Dew, married Maggie Thompson, 22, daughter of Enos and Elis Thompson, at Thompson’s father’s residence.

On 4 December 1889, Alfred Dew, 50, of Wilson township, son of Jack and Olive Dew, married Eveline Mitchel, 35, of Stantonsburg township, daughter of Olive Kilabrew, at F.W. Barnes’ farm, Stantonsburg.

On 4 January 1893, James Alston, 21, son of Charles and Anna Alston, married Martha Dew, 21, daughter of Alfred Dew, in Wilson.

On 17 January 1894, C.D. Dew, 24, of Wilson County, son of Alfred and Susan Dew, married Cora Wells, 18, of Wilson County, daughter of Jason and Ellen Wells, at Jason Wells’ residence in Cross Roads township, Wilson County. [Needham Dew changed his name to Cornelius D. Dew.]

On 28 June 1898, Reddick D. Dew, 30, of Wilmington, whose father Alfred Dew lived in Wilson and whose mother Susan was deceased, married Addie J. Cash, 30, daughter of John and Martha Cash of Wilmington.

George White, 34, of Craven County, son of Louisa Dew, married Lucinda Parker, 20, of Craven County, on 27 December 1898 at Jackson Dew‘s residence in Wilson township, Wilson County. Alfred Dew applied for the license, and Baptist minister J.T. Deans performed the ceremony in the presence of James T. Alston, L.A. Allen, and Jackson Dew.

On 9 May 1900, Alfred Dew, 55, of Wilson County, son of Jack and Olive Dew, married Margarette Hinton, 48, of Wilson County, at her house in Wilson. Henry Cotton applied for the license, and Baptist minister Fred M. Davis performed the ceremony in the presence of Mamie E. Parker, Lee Simms, and Mary Simms.

In the 1900 census of Wilson township, Wilson County: day laborer Alfred Dew, 50; wife Maggie, 47; sons Hassell, 14, and Will, 13, and stepson Charlie Hinnant, 14, day laborer.

On 4 March 1903, Alford Dew, 56, son of Jackson and Olif Dew, married Laura Watson, 45, at Watson’s residence in Wilson. Charles Oats applied for the license, and Baptist minister Fred M. Davis performed the ceremony.

In the 1910 census of Wilson, Wilson County: on Viola Street, Alfred Dew, 63, street laborer; wife Laura, 54, laundress; and daughter Eva, 13.

On 24 May 1911, Hassell Dew, 26, of Wilson, N.C., son of Alfred Dew and Evalina Kilbrew, married Daisy Robinson, 25, of Winston-Salem, N.C., daughter of Samuel Robinson and Elvira [no maiden name listed], in Manhattan County, New York.

Alfred Dew died 23 August 1910 in Wilson. Per his death certificate, he was about 66 years old; was born in Wilson County to Jackson Dew and Olive Dew; lived on Viola Street; was married; and worked as a common laborer. Martha Aulston was informant, and he was buried in Wilson [likely, Oakdale or Odd Fellows Cemeteries.]

Martha Alston died 3 April 1929 in Wilson. Per her death certificate, she was born 10 March 1871 in Wilson County to Alford Dew and Barbray Woodard; was married to James Alston; lived at 507 East Green Street; and was buried in Wilson [likely, Vick Cemetery]. Rufus Edmundson was informant.

Redick Diew died 6 August 1933 in Wilson. Per his death certificate, he was 3 August 1868 in Wilson County to Alfred and Susan Diew; was a barber; was a widower; and resided at 1108 Wainwright Avenue. Eula Locus of the home was informant.

“Cornelius Dew (nick name) Needham Dew” died 30 July 1944 in Cross Roads township, Wilson County. Per his death certificate, he was born 1 May 1881 in Wilson to Albert [sic] Dew and Susian [maiden name unknown]; was married to Maggie Dew; and worked as a farmer.

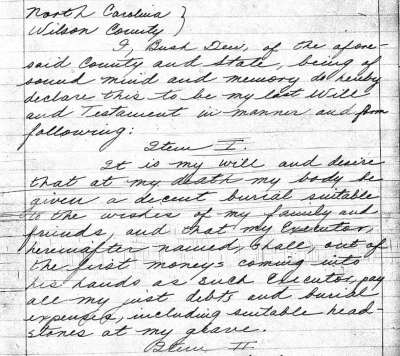

Will of Alfred Dew (1910), Wilson County, North Carolina, U.S. Wills and Probate Records, 1665-1998, http://www.ancestry.com.