Let’s talk about a city that’s doing cemetery preservation right.

My mother’s mother was from Statesville in Iredell County, in North Carolina’s western Piedmont. For decades, my great aunt Louise lived at 648 South Green Street, directly across from Statesville’s oldest public African-American burial ground, now known as Green Street Cemetery. I’ve only found three marked graves of my family members there — those of my great-great-grandfather John Walker Colvert, his wife Addie Hampton Colvert, and their daughter Selma E. Colvert — but there are certainly many more. My great-great-great-grandfather Walker Colvert, born on a northern Virginia plantation around 1819 and brought as a child to North Carolina as part of an inheritance. My great-grandfather Lon W. Colvert, a bootlegger turned respectable barber. My grandmother’s half-brother John W. Colvert II and his mother, Josephine Dalton Colvert. My grandmother’s aunts Addie McNeely Smith and Elethea McNeely Weaver and her cousin Irving McNeely Weaver, who was brought home from New Jersey for burial. Maybe her grandfather Henry W. McNeely, born to a slaveowner and his enslaved housekeeper.

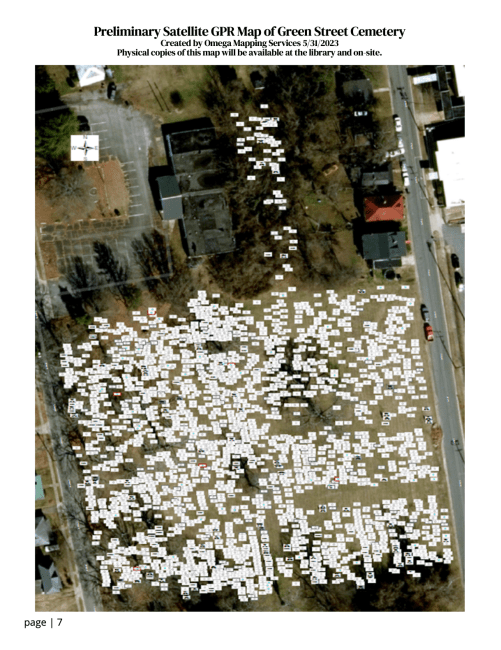

With so few grave markers, Green Street Cemetery seems relatively empty, but I have always assumed it was full. A local undertaker told me that, at sunset at the right angle in the right season, the shallow depressions of old graves stand out vividly in the landscape. This year, Iredell County Public Library, Iredell County, the City of Statesville, and the Statesville Chapter of the NAACP have partnered to locate and count Green Street Cemetery’s unmarked graves, to memorialize them, and to erect educational signage at the graveyard.

Imagine that. Local government at the forefront of efforts to preserve, honor and expand knowledge about an old cemetery.

In April, on its Facebook page, the Iredell County Public Library posted that it was “pleased to update the community on the continued preservation efforts at the Green Street Cemetery. Omega Mapping Services conducted a ground-penetrating radar survey from Friday, March 24, to Thursday, March 30. In that time, it has been determined that there are a total of 1,816 burials in the land that was surveyed. Of that number, 1,673 are unmarked, although several of those graves have stones that are covered over and will need to be extracted. The library plans to uncover these important stones in order to obtain vital information. The GPR survey is not complete and Omega will return to finish studying the property after additional clearing of the trees and brush in the extension of the cemetery located behind the old funeral home. [City of Statesville crews did the clearing, and the City’s mayor posted about its role in the project with the hashtag #promisesmadepromiseskept.] The completion of this part of the survey should take place this month.

“In addition to this, we are very excited to invite the community to join us for the next phase of this project through a hands-on program at Green Street Cemetery. As part of the $20,000 grant awarded by NC Humanities to the library for this project, we have purchased stainless metal markers to be installed at every unmarked grave in the Green Street Cemetery in place of the orange flags. This product came to us as a recommendation from the surveyor who has used these markers in other cemeteries. The marker consists of a ten inch (10”) bolt with a three and a half inch (3.5”) disk at the top. Once installed, it will lay flush with the earth allowing maintenance to continue as usual with no disruption or damage to the markers. In time, when the ground cover grows over the markers, they will still be identifiable with a metal detector, similar to markers used by land surveyors. They are easy to install by pushing the bolt into the ground by hand or using rubber mallets. With the amount of rain we are expecting in this area in the coming days, the ground will be soft enough to install these markers. Members of the community are encouraged to participate in this event, especially the descendants of those buried at this site.“

I.C.P.L. hosted meetings throughout late winter and spring to engage the public about the future of Green Street Cemetery and has involved the descendant community not only in planning, but in the execution of plans to memorialize the generations buried there.

Certainly, there are differences between Green Street Cemetery and Vick Cemetery. Green Street never lapsed into a jungle, and the City of Statesville has maintained it since 1961. Green Street’s lost grave markers have fallen to time and the elements, not city-sanctioned removal and destruction. Nonetheless, though it sits in a much more uncomfortable seat vis-a-vis its responsibility for current conditions, the City of Wilson could take a page from Statesville’s book. Viewed cynically, the City has an opportunity to gin up good press (and, maybe, goodwill) with an engaged, enlightened, transparent approach to Vick. Instead, it continues to hide its hand in service of its own agenda. For a city desperate to market itself as a progressive, welcoming, attractive location for new folks and new business, it’s a curious strategy.

It’s also business as usual.

Wilson takes justifiable great pride in Whirligig Park, a burgeoning downtown, the YMCA, the Farmers Market, and the Gillette sports complex among other exciting developments, but is acutely tone-deaf to the perceptions of East Wilson residents that the City’s new prosperity does not extend across the tracks. When boneheaded ideas like closing the Reid Street Center pool (“kids can swim at the Y”) reach the light of day, the City is caught off-guard by the vociferous backlash and immediately backpedals, stuttering and stammering. When New South Associates formally reports to the City that graves lie under its power poles, the City will once again be on its collective back foot.

Seize this opportunity, City of Wilson. Engage the descendant community openly and honestly. Find out what people want to see happen at Vick. Accept responsibility. Listen. Learn. Reflect. Then act in accordance.

For more about the history of Green Street and collaborative efforts to preserve it, see Viewpoint: Recognizing the historical significance of the Green Street Cemetery, http://www.iredellfreenews.com. For coverage of ground-penetrating radar performed there, see Every burial is a story: Survey of Green Street Cemetery uncovering history, http://www.statesville.com; Up to 2,000 unmarked graves uncovered in Statesville, http://www.qcnews.com; and ‘This is holy ground’: Radar survey preserving history at Statesville cemetery, www.spectrumlocalnews.com.

Photo by Lisa Y. Henderson, 2014.