Wilson Daily Times, 17 May 1937.

——

- Shorty Best

- James Best

- Loraine Bynum

Wilson Daily Times, 17 May 1937.

——

At my request, the State Historic Preservation Office of North Carolina, Division of Historical Resources, forwarded a copy of its file on Yelverton School. It’s a slim folder containing four pages: a Historic Property Survey Summary; N.C. Rosenwald School Search Form; and two print-outs from the Fisk University Rosenwald Fund Card File Database.

Yelverton School was built circa 1925 as a frame, side-gabled, two-teacher-type Rosenwald school. A front-gabled projecting wing was flanked by two recessed entries, and its windows were nine-over-nine and six-over-six sash.

The Fisk database print-outs contain two breath-taking photographs of Yelverton School, seemingly taken around the time the school was built. The first was taken straight-on, young pines standing in the background. The second shows the rear elevation.

An unidentified man approaches the school through what appears to be broomsedge.

Fisk’s Rosenwald database is undergoing digitalization; I look forward to closer examination of these images when available online.

Yelverton School is gone.

One of only three official Rosenwald Schools still more-or-less standing in Wilson County, it was recently demolished.

I understand the building was in bad shape, but wish its owner had reached out beforehand to discuss features from its historic interior that might have been salvaged.

Photo by Lisa Y. Henderson, December 2023.

Like other white Primitive Baptist congregations, Saratoga’s White Oak Primitive Baptist admitted African-Americans to segregated membership — probably from the time it was founded in 1830. However, when they were able to form their own congregations after Emancipation, most Black Primitive Baptists left white churches to worship in less discordant settings, and White Oak’s members joined African-American churches in southeast Wilson County, including Bartee and Cornerline.

White Oak P.B. is no longer active. A small cemetery lies adjacent to the church, but its graves are relatively recent. (The oldest marked grave dates to 1927.) It seems likely that prior to that time, church members were buried in family cemeteries in the neighboring community.

White Oak Primitive Baptist Church, Saratoga, Wilson County.

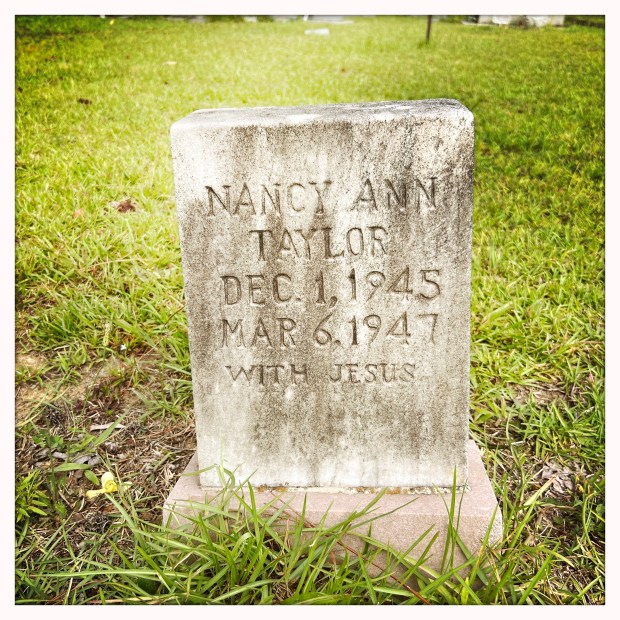

On a recent visit to White Oak, I was surprised to recognize a feature in the graveyard. Up to then, of hundreds I’ve found, I had never seen a Clarence Best-carved marker on a white person’s grave. Here, though, was a little cluster, a single family whose small marble headstones I immediately recognized as Best’s work. They tell a terrible tale of loss, four babies who died before they reached the age of two.

Photos by Lisa Y. Henderson, August 2023.

Wilson Daily Times, 16 September 1950.

Clipping courtesy of J. Robert Boykin III.

Daniel, a tall, handsome, dark-skinned man, left William Barnes’ plantation near Oak Grove [Saratoga] on the night of 20 September 1834. Eleven months later, Barnes began running ads in the Tarboro Press, offering a $50 reward for Daniel’s capture. Despite specific details about Daniel’s physique, his mother and siblings (from whom he had been separated when sold by Asahel Farmer), and even his father (a blacksmith who worked nearly independently in Nash County), Daniel was still on the lam in May 1936 when this ad ran, and as late as April 1837, when the Press re-printed it.

Tarboro’ Press, 7 May 1836.

Four years later, Abner Tison, another Saratoga-area planter, offered a reward for a Daniel whose physical description closely matched the Daniel above. He’d been missing a year. Though the ages are off, this Daniel had some notable scars, and was said to have been raised in Pitt County, this is surely the same knock-kneed man, bound and determined to take his freedom.

Tarboro’ Press, 24 July 1841.

Wilson Daily Times, 26 June 1941.

County Extension Agent Carter W. Foster published a reminder of the annual county-wide picnic for farm families, held in 1941 at Yelverton School in far southeastern Wilson County.

The eighteenth in a series of posts highlighting the schools that educated African-American children outside the town of Wilson in the first half of the twentieth century. The posts will be updated; additional information, including photographs, is welcome.

Yelverton School

Yelverton School is listed as a Rosenwald School in Survey File Materials Received from Volunteer Surveyors of Rosenwald Schools Since September 2002.”

Location: A 1936 state road map of Wilson County shows Yelverton School on present-day Aspen Grove Church Road near the Pitt County line.

Per notification of public sale in 1951: “YELVERTON COLORED SCHOOL in Saratoga Township, containing two acres, more or less, and more particularly described as follows: BEGINNING at a stake on the East side of Aspin Grove Road beside a white oak, runs thence South 55 1/2 [degrees] East 204 feet to a stake with a sourwood and 2 pine pointers, corners, runs thence 34 1/6 [degrees] West 420 feet to a stake, corners, runs thence North 55 1/2 [degrees] to a stake on the easterly side of said road, thence with said road to the beginning. Being the identical land described in a judgment recorded in Book 179, at page 155, in the Office of the Register of Deeds of Wilson County.”

Yelverton School was built in 1925-26 with $700.00 from the Rosenwald Fund, $2025.00 from Wilson County, and $50.00 from local families.

Yelverton School building is one, and the better preserved, of two wooden Rosenwald schools more-or-less standing in Wilson County. Per Research Report: Tools for Assessing the Significance and Integrity of North Carolina’s Rosenwald Schools and Comprehensive Investigation of Rosenwald Schools In Edgecombe, Halifax, Johnston, Nash, Wayne and Wilson Counties (2007), in 1926, State Rosenwald Supervisor William F. Credle gave this report on the newly built Yelverton School to the Wilson County Board of Education:

“This is good two-teacher school with cloak rooms and industrial room. It is properly located on a good site. I recommend that the following improvements be made:

“Put in at least 30 feet of blackboard to the room. This should be provided with a chalk rail.

“Put in terra cotta thimbles in all chimneys.

“Provide good stoves. Jacketed stoves are to be desired. We furnish blue prints for jackets and they can be made for about $20.00 a piece at an good tinner’s.

“Hooks for cloaks and shelves for lunch boxes should be provided in the cloak rooms.

“The seats now in the building should be reconditioned and a sufficient number of new ones provided to accommodate the enrollment. The old seats that are badly cut can be put in very good condition by planing off the rough tops and staining and varnishing.

“Finally the privies should be removed to the line of the school property. They should be provided with pits and the houses should be made fly proof.

“The patrons should be encouraged to clean off the lot so as to provide play ground for the children.”

The condition of Yelverton School has declined considerably in the 13 years since Plate 256, above, was published in the research report.

A bank of nine-over-nine windows.

One of the two classrooms. Note the stove and original five-panel door.

The rear of the school.

Known faculty: teachers Otto E. Sanders, Esther B. Logan, Merle S. Turner, Izetta Green, Louise Delorme, Dorothy Eleen Jones.

Plate 256 published in the Research Report; other photos by Lisa Y. Henderson, September 2020.

The sixteenth in a series of posts highlighting the schools that educated African-American children outside the town of Wilson in the first half of the twentieth century. The posts will be updated; additional information, including photographs, is welcome.

Healthy Plains School

Healthy Plains School is not listed as a Rosenwald School in “Survey File Materials Received from Volunteer Surveyors of Rosenwald Schools Since September 2002.” Nor is it listed in Superintendent Charles L. Coon’s report The Public Schools of Wilson County, North Carolina: Ten Years 1913-14 to 1923-24.

Location: A 1936 state road map of Wilson County shows Healthy Plains School on present-day U.S. 264 Alternate, just west of the Greene County line near Spring Branch Church Road.

Description: This school was likely named for (and near by) Healthy Plain Primitive Baptist Church, an African-American church (to be distinguished from a white church of the same name near Buckhorn in western Wilson County).

Known faculty: teacher Mary Estelle Barnes.

The fourteenth in a series of posts highlighting the schools that educated African-American children outside the town of Wilson in the first half of the twentieth century. The posts will be updated; additional information, including photographs, is welcome.

Saratoga School

Saratoga School is listed as a Rosenwald school in “Survey File Materials Received from Volunteer Surveyors of Rosenwald Schools Since September 2002.” This school was consolidated with other small schools in 1951, and its students then attended Speight High School.

Location: Per a sale advertised in the Wilson Daily Times for several weeks in the fall of 1951, “SARATOGA COLORED SCHOOL in Saratoga township, containing two acres, more or less, and more particularly described as follows: BEGINNING at a stake in the Saratoga-Stantonsburg Road, thence Northwest 140 yards to a stake, thence Southwest 70 yards parallel with said road thence Southeast 140 yards and parallel with the first line in the said Saratoga-Stantonsburg Road, thence with the said road 70 yards to the beginning. Being the identical land described in a deed recorded in Book 157, at page 70, Wilson County Registry.”

The school has been demolished.

Description: This school is described in The Public Schools of Wilson County, North Carolina: Ten Years 1913-14 to 1923-24 as a one-room building on two acres.

Known faculty: teachers Alice Mitchell, Naomi Jones, Mary E. Diggs, Corine l. Francis, Katie J. Woodard, Mary J. Lassiter.