In 1897, Malinda Hinnant filed for a Civil War widow’s pension on the basis of her husband Amos Hinnant’s service in Company K, 14th United States Colored Volunteers, Heavy Artillery.

Here — drawn from Malinda Hinnant’s widow’s pension file — is the sorry story of what happened after.

First, Malinda’s claim: on 16 July 1897, Malinda Hinnant, 53, appeared before notary public Sidney A. Woodard to make a declaration in support of her claim for a pension. According to the document, written by Woodard, she stated that she was the widow of Amos Hinnant, who had enrolled on 10 April 1865 in Company K, 14th Regiment, United State Colored Troops, Heavy Artillery. Amos was honorably discharged on 10 December 1865 at Fort Macon, North Carolina. Malinda, then a Barnes, married Amos Hinnant about 1867 in Wilson County, and it was a first marriage for both. Amos died 7 July 1897, and she had not remarried. Malinda appointed Frederick A. Woodard as her attorney for the claim. Her post office address was Taylor, Wilson County, and she no means of support beyond her daily labor. She signed the claim with an X in the presence of witnesses J.C. Hadley, a merchant, and L.H. Peacock, a school teacher.

Jacket of Malinda Hinnant’s petition.

An introduction: Sidney A. Woodard and Frederick A. Woodard were brothers and law partners. At the time Malinda Hinnant filed her claim, Frederick was fresh off a humiliating loss to George H. White, his African-American opponent for a seat in the United States Congress. Per Sidney Woodard’s obituary, published 1 August 1915 in the Greensboro Daily News, he “from early manhood showed had showed a considerable business capacity. At the time of his death he owned several farms, was a large stockholder in the Wilson cotton mills, the Contentnea Guano factory, the P.L. Woodard company and the Briggs hotel.”

In July 1899, Malinda’s claim was approved, the Bureau of Pensions cut her a check, and the Woodards tried to steal her money. Malinda fought back, firing off a letter of complaint to the Bureau of Pensions. Less than a month later, Special Examiner I.C. Stockton arrived from New Bern to investigate.

Malinda Hinnant’s complaint.

Malinda Hinnant gave a deposition on 12 September 1899 at Taylor. She stated that since her claim had been investigated in May 1899, she had received only two pieces of mail from the pension commissioner. One was a letter dated 26 August 1899 in response to an inquiry about her claim from United States Congressman George H. White. The second was from the United States Pension Agent at Knoxville, notifying her that her inquiry had been referred to headquarters. She had not yet received a cent of her pension. Her son Haywood was in Wilson in mid-June 1899 and Sidney Woodard (“S.A. Woodard he signs his name”) told him her claim had been allowed. When Haywood said Malinda was unable to come to town, Woodard said he would go out to their house to “fix up the matter.” About the second week of July, Woodard came to her house to have her execute papers for the pension. She knew what the papers were only by what Woodard told her as she could not read and he did not read them to her. She said she had always signed whatever papers Woodard brought her and knew only what he told her. Woodard told her the papers had to be signed before she could get her money. He would send them off, and she would receive a check at the Taylor post office in a few days. Haywood and Spicey Jane Adams [sic, Atkinson] witnessed her make her mark. She was not sworn beforehand. James Barnes is the postmaster at Taylor. She never authorized Woodard to get any mail for her. She never authorized James Barnes or his wife to give Woodard her mail, and she did not know how Woodard got it. Woodard visited her again in late July 1899. He had some more papers for her to sign and left a yellow slip of paper. He explained that they were for her quarterly payments. He also said he had a check for $159 and some cents, but would have to have $25 out of it for him and $50 for his brother Fred Woodard. He said she owed them this amount for “the writing and work they had done” to get her pension. “I told him that I had had nothing to do with his brother Fred and that I did not owe Fred anything.” Woodard responded that Fred had done the “court work” and both would have to be paid. She refused to pay, and he asked how much she would give him. “I finally offered ten ($10) dollars and he just hooted at me & said he would have to have twenty five ($25) dollars or nothing, so he went off without the check doing anything about it.” He was holding a piece of paper that he said was her check. Bryant Hinnant, James Price, Bettie Boykin and her son Haywood were present. She had not seen Woodard since. Malinda asked B.A. Scott to go to Wilson with her son “to do the best they could for me.” She did not owe either Woodard any debt. Sidney Woodard prepared her pension application. Simon Barnes, the postmaster at Meeksville, North Carolina, executed all her affidavits, and Malinda paid him for some. Barnes told Haywood that he would not charge her for making out the other papers and, if she got a pension, she could pay him what she chose. Sid. Woodard never told her what he would charge to get her pension. She tried to get him to make an agreement, but he would not. “He said we would not fall out about a fee.” She did not know whether Woodard had received a fee from the government. Malinda signed her deposition after it was read to her, and Haywood Hinnant and his wife Esther signed as her witnesses. (Special Examiner Stockton, who took all the depositions in this matter, rated Hinnant’s reputation as “good.”)

Malinda’s son (and Amos Hinnant’s stepson) Haywood (or Howard) Hinnant, 36, gave a deposition on 12 September 1899 at Taylor, Wilson County. He said sometime in June 1899 he met Sidney Woodard on the street in Wilson, and Woodard told him his mother’s claim had been approved. He asked Haywood to bring his mother to Wilson, but Haywood said she could not sit up. Woodard agreed to go to her to “fix up her papers.” Woodard came out to the Hinnants’ home the second week in July bearing a pension certificate and pension vouchers for her signature. She was to receive $159.07. Malinda signed with a mark, and Haywood and Spicey Jane Atkinson signed as witnesses. Woodard said Malinda would get her money in eight to ten days. At the end of July, Haywood saw Woodard in Wilson on a Saturday morning. “I told him I thought the 8 or 10 days were a long time coming around & that I had a mind to write to the Pension Agent about the money.” Woodard said that was not necessary, that he had the check. Haywood asked what Woodard was going to charge his mother for getting the pension, and Woodard asked what she was willing to pay. Haywood “told him that as he was doing the work he ought to say what he would do it for.” Woodard said he would come to their house the next Sunday, and they would discuss fees then. Woodard and his wife showed up the following Sunday. Woodard stood on the “front piazza” and completed some paperwork that Malinda, without being sworn, signed with an X. Betty Boykin signed the vouchers as a witness. Bryant Hinnant was there, too. Haywood did not read the vouchers and did not know how they came into Woodard’s possession. His mother never received them through the mail. Woodard claimed they called for Malinda to be paid $24 quarterly payment. As of the date of his deposition, Malinda had not received a cent. Malinda never authorized Woodard to receive her mail or the postmaster to deliver her mail to Woodard. Nor had Woodard been authorized to collect her pension money. After Malinda signed the vouchers, Haywood again asked Woodard his fee. Woodard said he wanted $25, and his brother Fred. Woodard, as a lawyer licensed to practice before the Bureau, should get $50. “He admitted that that the law would not give him anything, but he thought he ought to have something …” “I told him I did not know that his brother Fred. was entitled to anything as mother had not employed him. I also told him that mother was willing to pay him what the law allowed him.” Woodard said the law did not allow him anything, but he thought he should get $25. Haywood asked if the government had not already paid him $10. Woodard said no, that he could not practice before the Bureau. “He further said if my mother would not pay him anything he would have to get along with his brother getting the fifty ($50) dollars …” Woodard said he had enough money to pay Malinda her pension if she would give him $25 and his brother $50. Malinda refused. Woodard left, saying Haywood could pick up her pension money, minus Fred’s $50, in Wilson next week. The following week, Haywood went with B.A. Scott to Woodard. Scott demanded that Woodard pay him Malinda’s pension money. Woodard said he would pay it with a discount of $50. Scott said he could accept that and asked if Woodard had not received a $10 fee from the government. Woodard said no. Before they left Wilson, Scott consulted another lawyer, who advised them to pay Woodard $25 “to save trouble.” Scott and Haywood returned to Woodard and offered to allow him $25 to settle the matter. Woodard refused. Haywood acknowledged that he had never made a demand to Woodard to turn over the check. He also stated that they had never had dealings with Fred Woodard and did not recall whether his name was mentioned in his mother’s pension application. Malinda Hinnant did not owe debts to either Woodard. Haywood owed Sidney Woodard $5, which he agreed to pay when Malinda received her money. “My mother lives with me & I am interested in getting what is justly due her.” Haywood Hinnant signed his deposition after it was read to him. (Special Examiner Stockton rated Hinnant’s reputation as “good.”)

B.A. Scott, deposed 12 September 1899 at Taylor, stated that in early August sent for him concerning her pension. She told him that Sidney Woodard had her pension, but would not give it to her, and she wanted him to go to Wilson with Haywood Hinnant to see what could be done. He and Haywood visited Woodard about the second week in August. Woodard said they get the money if they paid him $25 and his brother $50. He said that because he was not entitled to practice before the Bureau, he was not entitled to payment unless they gave him some. Scott said he could not understand about the $50, but could give him $10, which was what he understood that the government allowed attorneys in claims. Scott then consulted with other lawyers in town and was told he should settle for $25. Scott went back to Woodard and offered $25, which he refused, “saying he would not work for nothing and if he could not get fifty ($50) dollars he would hold on to the check & wait a while …” Scott did not see the check and did not make a demand for it. He did not know how Woodard got possession of Malinda’s check. Scott was neither related nor interested in the claim. He signed the deposition after it was read to him. (Special Examiner Stockton rated Scott’s reputation as “good.”)

Spicey Jane Atkinson, deposed on 12 September 1899 at Taylor, stated that she was 16 years old and had known Malinda Hinnant several years as a neighbor. She had heard that Malinda was trying to get a pension. On a Tuesday in July 1899, she was passing by Malinda’s house and was asked to come in and witness her signature by mark on some papers. She was told they were pension papers, but did not recall if they were read to her. “There were two papers if I make no mistake and I signed each one in two different places.” Haywood Hinnant signed, too. Spicey did not ask any questions about the papers and did not see Malinda sworn. Malinda asked “Mr. Woodard” what he was going to charge her, and Woodard asked what she would be willing to pay. Malinda said “she supposed the law allowed him ten ($10) dollars,” and Woodard said he had not been allowed anything. Woodard left, saying he would be back in a few days. She was not at the Hinnants’ house again with Woodard. She is neither related to Malinda nor interested in her claim. Spicey J. Atkinson signed her deposition after it was read to her. (Special Examiner Stockton rated Atkinson’s reputation as “fair to good.”)

J.W. Barnes, deposed on 13 September 1899 in Taylor, stated that he was 48 years old and had known Malinda Hinnant all his life. “She nursed me when I was a child.” He was the postmaster at Taylor, Wilson County. There are no pensioners who receive mail at this post office. Haywood Hinnant generally gets his mother’s mail “as she has not been able to go out for a long time, being confined to the house sick.” A few times, when Haywood requested, he gave her mail to Ransom Hinnant, son of her nearest neighbor. Barnes knew Sid Woodard, but Woodard had never been to his house and he had never given Woodard any of Malinda’s mail. He heard that Woodard has Malinda’s pension check and will not give it up unless she pays him $75. He did not know how Woodard got the check, but was positive it was not through the Taylor post office. Barnes is not related, interested or biased in the matter. Malinda Hinnant “is a very reliable and worthy woman and I am interested in her getting a pension if it be justly due her.” Barnes signed his deposition. (Special Examiner Stockton rated Barnes’ reputation as “good.”)

Bettie Boykin, deposed on 12 September 1899 in Taylor, stated that she was 22 years old. She said that on the first Sunday in August 1899, she called at Malinda Hinnant’s house to see how she was getting along. She found Sidney Woodard and his wife there, as well as Haywood Hinnant and James Price, a neighbor. Woodard asked Malinda to sign her by mark on some papers, and Boykin signed as a witness. She signed two different papers in two places, as did James Price. Woodard did not ask her any questions about Malinda and did not read the papers to any of them. She did not know what they were about. She did not remember Woodard swearing Malinda to an oath. Woodard said his brother was to have $50 and if Malinda did not pay him (Sidney) $25, she “need not pay him anything.” She did not know if Woodard had the money, but heard him say something about having the pension check. Boykin thought Woodard offered to pay Malinda $105. She was not sure, but thought Woodard told Malinda that the amount due her was $183.07. Woodard did not pay Malinda any money in her presence. He took the papers and left. She recalled that this was the first Sunday in August “because I was to go to church with my brother that day and did not go.” Boykin was not related nor interested in the claim. She signed her deposition after it was read to her. (Special Examiner Stockton rated Boykin’s reputation as “fair to good.”)

Bryant R. “B.R.” Hinnant, deposed 12 September 1899 in Taylor, stated that he was 46 years old. He said that sometime in late July 1899 Haywood Hinnant told him he was having some trouble with Sidney Woodard about her pension. Haywood asked Bryant to come down to his mother’s house when he saw Sidney Woodard pass the following Sunday. When he saw Sidney Woodard and his wife pass by, he followed as requested. Malinda came out on the porch and sat down. Woodard took some papers from his pocket “and went to writing.” He then asked Malinda to sign by mark. He asked Bryant to witness, but “as I do not write my name,” he had James Price and Betty Boykin sign. Bryant supposed they were pension papers, as Woodard Malinda that she would have $24 more by the next Friday. Malinda was not sworn at all, and Woodard did not read the papers to her. Woodard told Malinda her check was for “one hundred and fifty odd dollars” and he had enough money with him to cover it, but she should pay him $25 and his brother $50. Woodard said the law did not allow him anything, but did allow his brother $50 because he was a registered lawyer. Malinda asked if he would take $10 and he said no, if he could not gave $25, he would not take anything. Woodard turned to Bryant and said he had worked two years for this pension and thought if it was worth anything it was worth $25. Malinda refused to pay. and Woodard carried the check and other papers off with him. Bryant did not know anything else, and was neither related nor interested in the claim. He signed his deposition with an X after it was read to him. (Special Examiner Stockton rated Hinnant’s reputation as “good.”)

Levi H. “L.H.” Peacock, deposed on 13 September 1899 in Wilson, stated that he was 40 years old and a clerk in the post office at Wilson. About a month before, the post office received a letter addressed to Malinda Hinnant at Meeksville, Wilson County, and forwarded to Wilson. The letter was placed in Frederick Woodard’s post office box. F.A. Woodard and S.A. Woodard were law partners in Wilson. Frederick Woodard has requested that if any mail came for Malinda, clerks should put it in his box. Peacock presumed that Woodard was Malinda Hinnant’s attorney in her pension claim, and for that reason delivered the letter to him. He recalled only one letter, which he thought was from the Bureau of Pensions. Peacock admitted that neither Malinda nor Haywood Hinnant had never ordered her mail delivered to either Woodard. Nor had Woodard ever told him Hinnant had authorized delivery of her mail to the Woodards. Peacock was not related or interested in the claim. He signed his deposition. (Special Examiner Stockton rated Peacock’s reputation as “good.”)

The file contains only the first page of the statement of James “J.M.” Price, deposed on 12 September 1899, at Hawra, Wilson County. He stated that he was 27 years old and had known Malinda Hinnant only since January 1899. Haywood Hinnant told him that Sidney Woodard had a pension check belonging to his mother and “it looked like Woodard was not going to give it to her.” One Sunday in late July or early August, Price was at B.R. Hinnant’s to see about some work when Woodard drove by. Bryant Hinnant asked him to go with him to Malinda Hinnant’s house to see what Woodard had to say. When they arrived, Woodard had just gotten out of his buggy and was talking to Haywood about a pension check. He took some papers from his pocket, wrote on them a while, then had Malinda sign. He did not read the papers aloud. He asked Bryant Hinnant to sign, but as he “cannot write good,” Price and Betty Boykin signed.

The file is also missing the first page of the statement of Sidney A. Woodard. Beginning at page 2, he stated that fee agreements were not executed initially, but on 18 July 1899, Malinda Hinnant signed an agreement to allow a $25 fee. He did not file the fee agreements because he did not want to delay payment of Hinnant’s money, but provided them in Special Examiner Stockton during this investigation. When the check came, he took it out to Hinnant, who endorsed it and directed him to cash it. He was to deposit the check and pay the amount, minus $50, to whomever came to collect it. The next day B.A. Scott went to see him. Woodard was sick in bed and his brother was away. In a day or two he deposited the check. Scott and Haywood Hinnant went to see him about the money, Scott said Malinda was dissatisfied about the $50. As Frederick Woodard was away, he could not settle for less. They left and said they would see further about it. Later that day, Woodard saw Scott on the street and Scott said he would give him the $25. Woodard again said he had no authority to settle for less than $50. Since then, he had no further contact with the Hinnants. He supposed the check had been collected, but had not checked with the bank. He knew Hinnant intended to write to the Bureau about it, so he was waiting to hear from them to explain his position. When he found out the Hinnants were not satisfied, he he went to the bank to withdraw the check, but learned that it had been forwarded for collection. Since his brother had been paid $10, and since he was informed that the duplicate fee agreements Fred obtained were invalid, he would go the next day to pay Malinda Hinnant the full amount of the check and send a receipt to Stockton at New Bern. Woodard signed his deposition. (Special Examiner Stockton rated Woodard’s reputation as “said to be questionable in money matters.”)

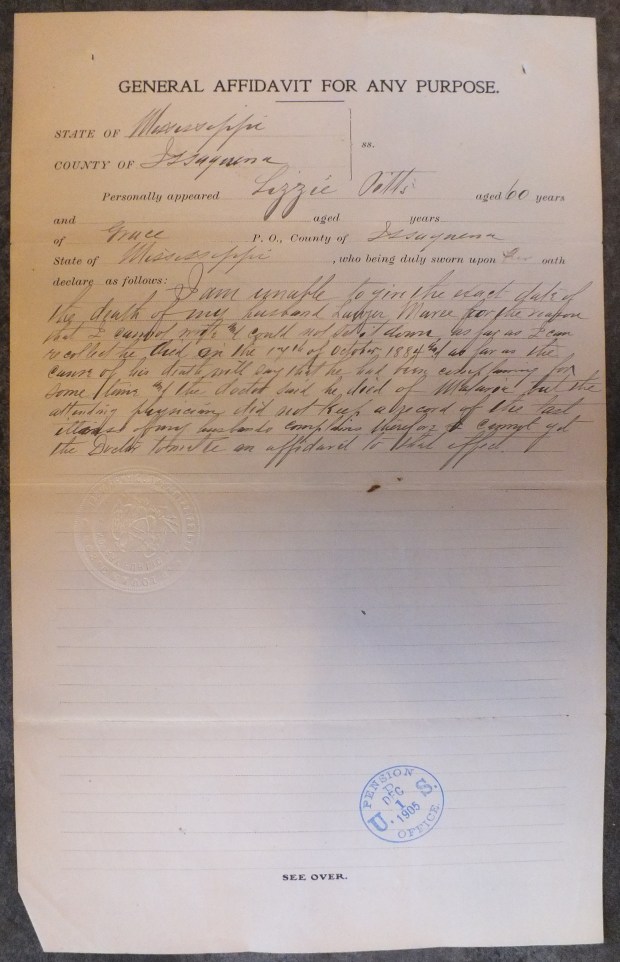

The fraudulent fee agreement.

Despite his sworn statement to make things right, Woodard had further tricks up his sleeve, necessitating that Special Examiner Stockton travel to Wilson for a second round of depositions.

Haywood Hinnant gave a deposition in Wilson on 19 December 1899. He was 36 years old and resided at Taylor, Wilson County. He started with a clarification. “My correct and proper name is Howard Hinnant. When I was a boy in school my teacher taught me to sign my name H.W. Hinnant. I have been called “Haywood” Hinnant ever since I can remember. Quite a number of my acquaintances call me “Wood” Hinnant — a nickname for short — but my father gave me the name Howard. My father died when I was small and my stepfather, Amos Hinnant, gave me the name Haywood Hinnant and I am called Haywood Hinnant by most people. In signing the papers in my mother’s claim I have always signed my name Haywood Hinnant.” He showed the examiner an envelope from the Treasury Department addressed to Haywood Hinnant and stated that he did not believe he had ever signed any papers for Sidney Woodard as “Howard Hinnant.” His mother Malinda Hinnant died 13 November 1899. On 15 September, Sidney Woodard came to his house to pay his mother the money due her as the first payment of her pension. Malinda Hinnant was at Lewis Stott’s home that day, and Haywood and Woodard went to Stott’s. Woodard told her he had brought her $155. Haywood asked if had made a mistake in the amount, and Woodard said no. Haywood said Woodard had showed him a check for $159 and, he believed, 41 cents. Woodard denied it. When Haywood said he could prove it, Woodard said he had made a mistake and the amount was only $155. (But if Haywood could prove it, he would give him the four dollars.) He then asked Malinda how much she was going to give him. “My mother told him she was not willing to allow him anything.” Woodard then asked Haywood if he thought his mother should give him something. Haywood asked if he had not already gotten what the law allowed. Woodard said his brother had gotten $10, but he, who had done all the work, had received nothing. He repeated his demand for $25. “So after much persuading, mother finally agreed to pay him a fee of twenty-five ($25) dollars.” Woodard also deducted the $5 Haywood owed him and gave Malinda $125. Haywood and Malinda then signed some kind of receipt. He was not sure whether he read the receipt, but did not believe it was in the amount of $159.07. Haywood went to Woodard twice after this, but Woodard said he had nothing more. Lewis Stott, his mother Rachel Stott, his daughter Effie Stott, and Haywood’s wife Esther Hinnant were present and heard Woodard demand $25 from his mother and pay her $125. When shown a receipt of Malinda Hinnant for $159.07 received from Sidney Woodard, Haywood acknowledged his signature but claimed it should show $155. “I remember particularly when Mr. Woodard started to go that I spoke about the amt. of the check being $159 and Mr. Woodard said not it was not. Then in a joking way I told him I would go him the treat if there were not $4 more coming to mother and he promised the same back to me.” Haywood remembered seeing the check in Woodard’s hands at his house. Bryant Hinnant, James Price and Betty Boykin were there. Malinda Hinnant did not endorse this check or authorize Woodard to collect the money for the check. Woodard filled out the voucher for her quarterly pension, but no one signed the check. Woodard did not show the check until he through writing and had put the papers in his pocket. He pulled it from an envelope in his pocket as he prepared to leave. He, Price and Bryant HInnant looked at the check, but his mother did not endorse it. The first time Woodard came to his house was a Tuesday in Juily. Haywood and Spicey Atkinson witnessed her signature on the voucher, but he did not read it. Woodard told him it had to be signed and returned before Malinda could be paid. He thought he signed his name ‘Haywood Hinnant’ and believed the signature was genuine. He also examined his signatures on the fee agreements. If he signed them, he did not know what he was signing as his mother never agreed to pay any fee to Woodard. “The more I look at the voucher the second place where I signed with Spicey J. Atkinson does not look like my handwriting — neither like mine not Spicey’s.” The other looked like his handwriting and he supposed he signed ‘Howard.’ He signed ‘Howard or Haywood Hinnant’ after the deposition was read to him.

The alleged receipt for $159.07.

Bettie Boykin’s second deposition was 21 December 1899 in Wilson. She stated that she thought she signed her name in three places on two papers, but could not say whether the papers were alike or not. Woodard did not read them to anyone, and she was not sworn. Nor were James Price or “Aunt Malinda.” She heard some conversation about Woodard having the check, but did not see it. She did not know if she wrote her name on the check or not. She believed she would recognize the papers if she saw them. When shown, she said “The first two signatures of my name are genuine. The third place where my signature appears I am not certain about. The signature does not look like my handwriting.” When shown the $159.07 check with her signature on the back, she said she did not remember seeing that paper before. She may have signed it, but did not remember seeing it. She did not know what any of the papers were that she signed. She signed the deposition after it was read to her.

J.M. Price gave his second deposition on 20 December 1899 at Hawra, Wilson County. He said he and Bettie Boykin witnessed Malinda Hinnant’s signature on a paper that Sidney Woodard said concerned her pension. He did not read it, and Woodard did not read it to Malinda. He signed only one document in two, or perhaps three, places. After the signatures, Woodard told Haywood and Malinda that he had the check and pulled it out of his pocket. Price stood near him and saw the amount of the check. It was for 140 or 150-odd dollars; he did not recall. Woodard said he had enough money to pay them if they allowed him $25 and his brother $50. The Hinnants would not do it, and Woodard put the check back in his pocket. Neither he nor Bettie signed the check. Price recognized his signature in four places on the voucher, but denied that two of them were valid. He could not swear that the signature on the $159.07 check was not his, but had no recollection [“it has passed my remembrance entirely”] of signing a check. He was not sworn to the paper he signed as he “would not be qualified to any paper on Sunday.” He signed the deposition after it was read to him.

The falsified voucher.

Lewis Stott was deposed at Taylor, Wilson County, on 20 December 1899. He had known Malinda Hinnant all his life and had been living on the same farm near her during the past year. She died 13 November. Stott remembered that Special Examiner Stockton had been to see Malinda about three months ago, that Haywood had gone to Wilson with Stockton , and that Woodard had come to visit Malinda two days later. She was visiting at his house, and Woodard paid her $125 in his presence. He saw Woodard and Haywood count the money. “Mr. Woodard talked so nice to them and pleaded so hard that Aunt Malinda finally agreed to pay him” $25 for his services. He also thought Woodard kept $5 that the Hinnants owed him. He heard Haywood talking to Woodard about a difference of $4. He did not understand the particulars, but heard Woodard say he had books to show the amount and if more were due he would pay it to Haywood next time he came to town. He was neither related nor interested in the claim and signed his deposition with an X after it was read to him.

W.E. Warren was deposed at Wilson on 20 December 1899. He was 42 years old and the cashier at First National Bank in Wilson. “Check no. 260,885 on the Assistant Treasurer of the United States at New York, N.Y. which you have shown me, dated Knoxville, Tenn., July 25th, 1899” was presented for collection by Sidney A. Woodard, if he was not mistaken. The bank’s books showed that Woodard received credit for the the amount of the check, $159.07, on 9 August 1899. Warren did not remember any particulars of the deposit. Woodard did regular business with the bank and made deposits almost daily. He signed his deposition.

Stockton passed his findings on to his superior, and on 11 January 1900 Commissioner H. Clay Evans issued a scathing report to the Secretary of the Interior. In summary: Sidney Woodard had both prepared Malinda Hinnant’s pension documents and notarized them. Woodard obtained her pension vouchers from the post office without permission, secured endorsements without her knowedge, and deposited a check for $159.07 to his credit. He then tried to get Hinnant to pay him and his brother $75 for their alleged services. When she refused, Woodard kept the check. When Hinnant complained, Special Examiner Stockton went to Wilson to investigate. Woodard claimed his demands for payment were made in ignorance of the law and promised to pay Hinnant immediately and to send Stockton a receipt. Afterward, Woodard paid Hinnant and gave her a receipt for $155, but again demanded payment of $25 for himself. “From the foregoing it is evident that the illegal fee of $25, demanded and received by Mr. S.A. Woodard, was a most flagrant violation of law. The same was demanded and received by him after notice from a Special Examiner of this Bureau that the demand, which had before the notice from the Special Examiner been made by Mr. Woodard, was illegal, and his excuse for having made the same in his deposition before the Special Examiner was that he did not know it was in violation of the law. Yet, within thirty days after said notice, he repeated his demand and accepted the money which was paid upon said demand.” The recommendation? “Institution of criminal proceedings against one S.A. Woodard of Wilson, Wilson Co., N.C.”

Unsurprisingly, the United States Attorney for the Eastern District of North Carolina declined to prosecute Woodard. Nonetheless, the steadfast bravery of Malinda Barnes Hinnant and her son Haywood Hinnant, who dared to challenge two prominent lawyers (one a former Congressman) saw them to justice.

——

- Amos and Malinda Barnes Hinnant — Amos was enslaved by Martha Hinnant. Amos Hinnant, son of Thomas and Charity Hinnant, married Malenda Barnes, parents unknown, on 5 March 1868 in Wilson County. (Amos’ mother Charity may have been enslaved by Martha Hinnant’s sister Mary Hinnant. On 14 July 1866, Charity Hinnant and Allen Williamson registered a cohabitation that had begun only the previous Christmas.) In the 1870 census of Spring Hill township, Wilson County: farm laborer Amos Hinnant, 30; wife Linday, 25; and sons Haywood, 9, and Burruss, 3. (The last three are described as white, which was almost certainly an error.) In the 1880 census of Spring Hill township: Amos Hinnant, 45, and wife Lendy, 34.

- Haywood Hinnant — In the 1880 census of Spring Hill township, servant Haywood Hinnant, 16, lived in the household of Bryant R. Hinnant next door to his parents Amos, 45, and Lendy Hinnant, 34. In the 1900 census of Cross Roads township: Haywood Hinnant, 36, wife Esther, 35, and Louis Freeman, 75. In the 1910 census of Cross Roads township, Haywood Hinnant, 46, wife Hester, 43, widowed mother-in-law Rachel Stott, 62, and lodgers Louis Freeman, 92, and Luther Fulton, 15, both laborers. Howard Hinnant died 10 October 1917 in Spring Hill township, Wilson County. Per his death certificate, he was born 10 August 1862 in Spring Hill township to Fielick Godwin and Lendy Barnes, was married, and was engaged in farming.

- Spicey Jane Atkinson — in the 1900 census of Spring Hill township, Wilson County: farmer Archabald Atkinson, 48, wife Martha M., 34, and children Mary F., 19, Spicy J., 17, Roxanna, 15, Narcissus, 13, Carline, 11, Minnie L., 8, Adline, 6, and Mattie M., 3. Spicey Jane Barnes died 25 September 1925 in Spring Hill township, Wilson County. Per her death certificate, she was born about 1884 in Wilson County to Archie Atkinson and Martha Shaw and was married to Joe Barnes.

- Bettie Boykin

- Lewis Stott — in the 1900 census of Spring Hill township, Wilson County: farmer Lewis Stott, 45, and daughter Effie, 15. Lewis Stott died 1 December 1918 in Cross Roads township, Wilson County. Per his death certificate, he was born about 1848 in Wilson County to Bunyan Grice and Rachel Stott and was a widower.

- James M. Price — James Price is listed as a 27 year-old farmer in the 1900 census of Spring Hill township.

- W.E. Warren — William E. Warren is listed as a 42 year-old bank cashier in the 1900 census of Wilson, Wilson County.

- B.A. Scott

- Bryant Hinnant — in the 1910 census of Spring Hill township, Bryant R. Hinnant, 46, wife Marry A., 53, son Mabry R., 18, and Earnest Deans, 23, a laborer.

- James “J.W.” Barnes — in the 1900 census of Old Fields township, Wilson County, James W. Barnes is listed as a 48 year-old farmer. He was the son of John H. and Maturia Barnes. In the 1860 federal slave census of Kirbys district, Wilson County, John H. Barnes is shown as the owner of eight people, aged 3 months to 34 years. The 16 year-old, who had cared for J.W. in his childhood, was Malinda Barnes Hinnant.

File #479,667, Application of Malinda Hinnant for Widow’s Pension, National Archives and Records Administration.