Tarborough Southerner, 18 October 1862.

David Williams’ slave labor camp straddled the Wilson/Edgecombe county line east of Town Creek. In October 1862, as the Civil War raged, Ashly turned his feet north and stole away toward freedom.

Tarborough Southerner, 18 October 1862.

David Williams’ slave labor camp straddled the Wilson/Edgecombe county line east of Town Creek. In October 1862, as the Civil War raged, Ashly turned his feet north and stole away toward freedom.

Tarboro Free Press, 5 December 1834.

$20 Reward.

RAN AWAY from the Subscriber, about four weeks ago, a mulatto fellow by the name of

MILES,

He is tolerable well built, full round face, when interrogated generally frowns and looks down — his father belongs to Major Whitmel K. Bulluck, and he has some relation at Charles Wilkinson, Esq’s. He is about 21 or 22 years old. It is probable he may attempt to pass as a free fellow, being quite intelligent. I will give the above reward to any person who will deliver him to me, or secure him in jail so that I can get him again, and pay all reasonable expences. W.D. PETWAY.

Town Creek, Edgecombe County, N.C.

Sept. 12, 1834.

——

A year and-a-half after advertising the sale of a dozen enslaved people, William D. Petway posted an ad seeking the return of an enslaved young man named Miles, whose intelligence was acknowledged and sense of self-worth implied in the wording of the notice.

Both Whitmel K. Bullock, who enslaved Miles’ father, and Charles Wilkinson, who held additional relatives, were farmers in the Town Creek area of what is now southwestern Edgecombe County.

Samuel Farmer stayed chasing runaways. Two weeks after disappearing into the inky darkness of a winter night, Davy slipped back into Farmer’s quarters to steal away his wife Malvina.

Tarboro Free Press, 19 February 1833.

$60 Reward.

RAN AWAY from the Subscriber, on Tuesday night, 22d January last, negro man

DAVY

Aged about 27 or 28 years, 5 feet 6 or 7 inches high, well built, dark complexion, has a scar about an inch and a half in length on the forehead near the hair, and several scars on his head. Davy came home clandestinely on Tuesday, 5th Feb. and took off with him his wife MALVINA, aged about 21 or 22 years, dark complexion and well grown. A reward of $50 will be given for Davy, and $10 for Malvina, if both or either of them be delivered to me, or secured in any jail so that I get them again. All persons are forewarned harboring, employing, or carrying off said negroes under penalty of the law. SAMUEL FARMER.

Edgecombe Co. Feb. 12, 1833

Tarboro Free Press, 22 September 1827.

$25 Reward.

RANAWAY from the Subscriber, on the 23d of July last, a Negro boy named GEORGE; he is about 17 or 18 years of age, 5 feet 6 or 7 inches in height, dark color, a pert lively look, and in speaking is apt to stutter a little; he has lost most of his fore teeth, and has two or three distinct scars on his throat, occasioned by a rising some time since. Said boy was purchased about eighteen months since, from Mr. Matthew Cluff, of Norfolk, at which place he was raised, but has frequently been to Elizabeth-City, in this State, and the boy said that he had been several times at sea. I expect that he will attempt to get either to Elizabeth-City or Norfolk. A reward of Twenty-Five Dollars will be given to any person who will apprehend said boy and lodge him in any jail, so that I can get him again. Masters of vessels and all other persons are hereby forbid harboring, employing, or carrying off said boy, under the penalty of the law. SAMUEL FARMER.

Edgecombe County, N.C. Septem. 4, 1827.

The Norfolk Herald and Elizabeth-City Star will please give the above three insertions, and forward the account to this office for collection.

——

In September 1827, Samuel Farmer, who lived in the area between Hominy and Toisnot Swamps, placed this ad seeking the return of an enslaved teenager who had run away in July. George was believed to trying to make his way back to Norfolk, Virginia, where he had grown up, or Elizabeth City, North Carolina, which he had often visited. (Four and a half years later, Farmer was chasing another young man, John.)

Daniel, a tall, handsome, dark-skinned man, left William Barnes’ plantation near Oak Grove [Saratoga] on the night of 20 September 1834. Eleven months later, Barnes began running ads in the Tarboro Press, offering a $50 reward for Daniel’s capture. Despite specific details about Daniel’s physique, his mother and siblings (from whom he had been separated when sold by Asahel Farmer), and even his father (a blacksmith who worked nearly independently in Nash County), Daniel was still on the lam in May 1936 when this ad ran, and as late as April 1837, when the Press re-printed it.

Tarboro’ Press, 7 May 1836.

Four years later, Abner Tison, another Saratoga-area planter, offered a reward for a Daniel whose physical description closely matched the Daniel above. He’d been missing a year. Though the ages are off, this Daniel had some notable scars, and was said to have been raised in Pitt County, this is surely the same knock-kneed man, bound and determined to take his freedom.

Tarboro’ Press, 24 July 1841.

Just months after Eugene B. Drake bought her in 1863, 23 year-old Rebecca was gone. Desperate to recoup his investment, Drake posted this remarkably detailed reward notice in newspapers well beyond Statesville. After precisely noting her physical features, Drake noted that Rebecca was “an excellent spinner” and “believed to be a good weaver, and said she was a good field hand.” (He had not had the chance to see for himself.) Rebecca may have helped herself to the products of her own labor, carrying away several dresses, as well as “new shoes.” Drake had purchased her from one of Richmond’s notorious slave dealers, but she was from Milton, in Caswell County, North Carolina, just below the Virginia line and southeast of Danville. There, Rebecca had been torn from her child and other relatives. Drake believed she was following the path of the newly opened North Carolina Railroad, which arced from Charlotte to Goldsboro, perhaps to seek shelter with acquaintances near Raleigh. He offered a $150 reward for her arrest and confinement.

Daily Progress (Raleigh, N.C.), 23 November 1863.

A year later, Drake was again paying for newspaper notices, this time for the return of his “slave man” Milledge, also called John, who had also absconded in new clothes and shoes. Drake again provided precise a physical description of the man, down to his slow, “parrot-toed” walk. Milledge/John had procured counterfeit free papers and a travel pass, and Drake believed he was aiming 200 miles south to Augusta, Georgia, probably on trains.

Carolina Watchman (Salisbury, N.C.), 28 December 1864.

I don’t know whether Drake recaptured either Rebecca or Milledge/John. If he did, the rewards he paid were money wasted. The Confederacy surrendered in April 1865, and thereafter he owned no one.

Dr. Algeania Freeman recently published Black River, a narrative of the life of her great-grandfather James Woodard. Accordingly to family lore and research, James Woodard was born enslaved in what is now Wilson County about 1850. After his father Amos was sold at auction and his mother died, Woodard ran away, eventually settling in Cumberland County. Dr. Freeman believes she may be descended from or otherwise related to London and Venus Woodard and is searching for proof of that connection. Her family has beaten the odds by maintaining a detailed oral tradition through several generations. Genetic genealogy may hold the key to recovering their Wilson County connection.

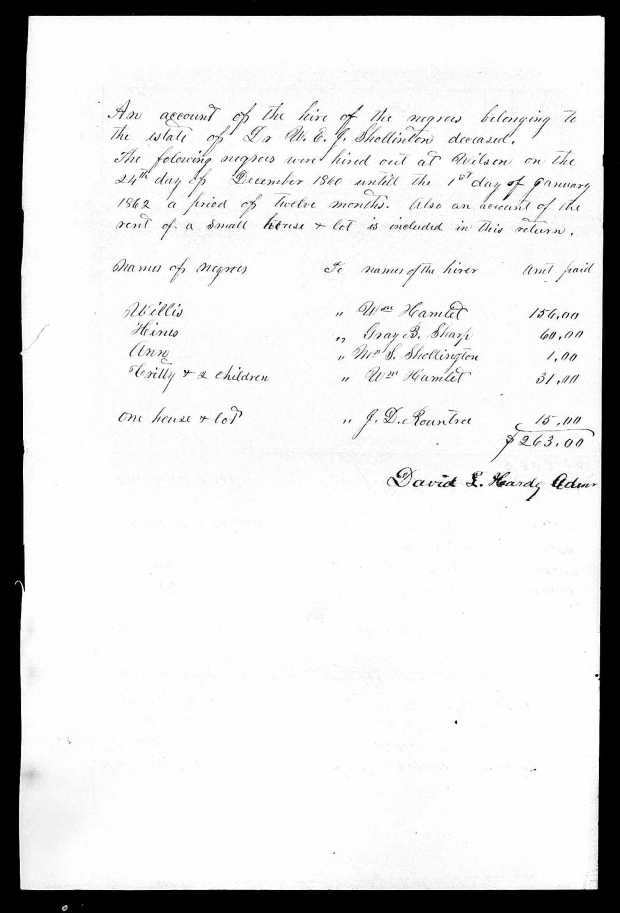

When Dr. W.E.J. Shallington died without a will at the end of 1860, his widow Sarah Shallington relinquished her right to administer his estate to David L. Hardy. The Shallingtons had minor children, and Hardy had the unenviable task of managing the estate to provide income for the family during the entirety of the Civil War.

Dr. Shallington held six people in slavery, and on Christmas Eve Hardy hired all of them out through 1 January 1862. Willis went to William Hamlet for $156.00; Hines to Gray B. Sharp for $60.00; Ann to widow Shallington for the nominal sum of $1.00; and Critty and her two children to Hamlet for $31.00. J.D. Rountree rented the Shallingtons’ house and lot in Wilson for $15.00

Though the account is not in the estate file, Hardy likely rented out the group 2 January 1862 through 1 January 1863 as well. The process repeated on 2 January 1863, with Willis, Hines, and Critty and her children going to J.H. Bullock and Ann remaining with Sarah Shallington. George Barefoot rented the house and lot at a cut rate.

The following year, the hiring out took place at Joyner’s Depot [Elm City] for the period of 28 December 1864 to 28 December 1865. (Or so the parties intended. Events at Appomattox would intervene.) Willis, Critty and her children went to Jordan Winstead at inflated rates (reflected also in the house rental); Ann, to Sarah Shallington. Hines, perhaps smelling freedom in the air, had “gone to the Yankees.”

With no enslaved labor to tap as a resource, by 1869 D.L. Hardy’s account of rentals contained a single line item: “6 March 1869, To amt rec’d for rent for house & lot from David Strickland cold. [colored] to Jany 1st 1870 $14.00. The house was vacant for 2 months as I could not rent it out at the 1st Jany 1869 on satisfactory terms.” Strickland renewed his lease on 1 January 1870 at an increase of four dollars a month.

——

In the 1860 census of Coopers township, Wilson County: Roda Shallington, 69; [daughter-in-law] Sarah, 36; and Mary Ann, 15, Caroline, 12, and Fredrick Shallington, 1. Roda claimed $5000 in personal property, and the rest of the Shallingtons, $3800. (This constant amount likely represented their (anticipated) inheritance from recently deceased W.E.J. Shallington.)

In the 1870 census of Wilson township, Wilson County: David Strickland, 30, farm laborer; wife Fillis, 28; and children Isaac, 2, Amanda, 12, and Samuel Strickland, 8; William Farmer, 1; and Jane Mosely, 9.

There are no Shallingtons, black or white, listed in the 1870 census of Wilson County. (In fact, I have found none of the men and women listed in W.E.J. Shallington’s estate using the surname Shallington.) However, in the 1880 census of North Wilson township, Wilson County, widow Sallie Shallington, 55, is listed as a member of an otherwise African-American household: Aaron Edmundson, 31, well digger; wife Ann, 26; and their children Earnest, 5, and Hattie, 3. (The census taker, perhaps startled by the unexpected arrangement, wrote a W over the B he initially recorded for her race. Also, this may be the Ann hired out above, if that Ann were a child.)

Estate Records of W.E.J. Shallington, North Carolina Wills and Probate Records, 1665-1998 [database on-line], http://www.ancestry.com.

Tarborough Southerner, 11 July 1857.

In July 1857, the Tarboro jailer advertised in a local newspaper that an enslaved teenager named Arch had been committed to jail. Arch, who had a scar on his wrist from being struck by a grubbing hoe, told Benjamin Williams that William J. Moore of Wilson County was his owner.

Tarborough Southerner, 28 February 1863.

Two years into the Civil War, Edmund Moore advertised in a Tarboro newspaper for the return of Jerry, a 30 year-old who formerly belonged to Howell G. Whitehead Jr. or Sr. of Pactolus township in eastern Pitt County, North Carolina.