Though strawberry picking is now regarded as a quaint pastime, suitable for Instagrammable photos of one’s toddlers, North Carolina’s strawberry fields were a labor battleground in the late 1930s.

We read here of three African-American Wilson women who were ruled in April 1938 to have committed fraud and misrepresentation for seeking unemployment benefits after refusing offers to pick strawberries.

A month later, the Daily Times reported a “mass strike” by potential pickers — more than 400 unemployed Black men and women who refused to accept job offers working in strawberry fields. When these workers filed for unemployment, they were charged with fraud and tried in mass hearings at which they faced fines and denial of benefits. “‘They seem to feel,’ said Herbert Petty, manager of the [employment] branch office [in Wilson], ‘that they would rather get $4 from us for not working than they would $10 a week by working for it.'” When asked what people would do without unemployment relief, Petty snapped: “‘They got along all right this time last year when they couldn’t get this insurance.”

The spring of 1939 saw the protest reemerge. Per the April 10 edition of the Daily Times, the Wilson employment office sent out a “hurry call” for strawberry pickers, who would be sent to fields near Warsaw and Wallace in Duplin County, 50 to 80 miles south of Wilson. The report noted that there was “nothing mandatory” about the first few calls for laborers, but later in the season the employment office might be “forced” to draft pickers from the ranks of applicants for unemployment. If this happened, and applicants refused to go, “official action would be taken against them.”

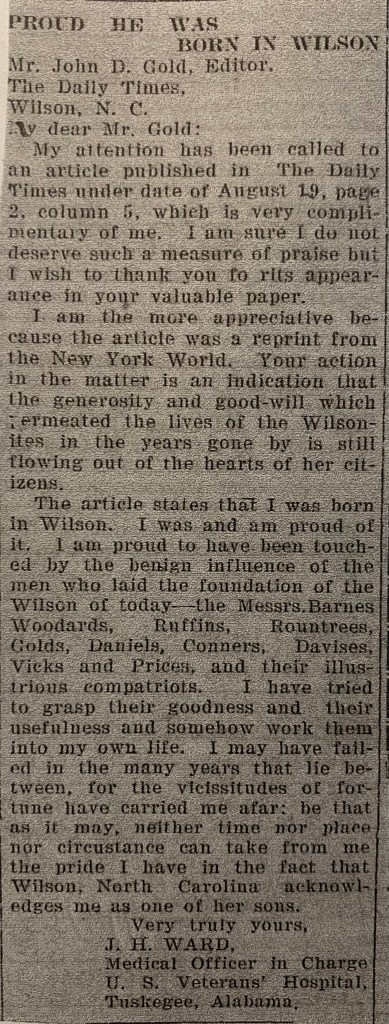

In response to Times columnist John G. Thomas’ dismissive takes on the motives and concerns of African-American laborers, Willis E. Prince submitted for publication this remarkable rebuke.

Wilson Daily Times, 13 April 1939.

Who was Willis Ephraim Prince? In 1939, he was a 53 year-old self-employed carpenter and bar owner who had spent a decade living in Philadelphia and New York City and whose financial independence allowed him to raise his voice in protest without fear of repercussion. Just as importantly, he was the son of Turner Prince.

In 1865, formerly enslaved men and women settled on the flats just across the Tar River from Tarboro; they called their community Freedom Hill. Pitt County-born freedman named Turner Prince (1842-1912) and his wife, Sarah Foreman Prince, soon arrived in the community. Prince, a carpenter, constructed houses and other buildings throughout Freedom Hill and involved himself in local Republican politics. In recognition of his leadership and literal community-building, Freedom Hill residents chose the name Princeville when the town was incorporated in 1885, the first town in North Carolina (and probably the United States) incorporated by African-Americans.

——

In the 1900 census of Tarboro township, Edgecombe County: carpenter Turner Prince, 58; wife Sarah, 54; children Laura, 18, Sarah J., 16, Willis E., 14, and Jonas A., 11; and granddaughter Lucy Lloyd, 9.

On 21 August 1907, William Prince married Gertrude Pittmon in Manhattan.

In the 1910 census of Manhattan, New York, New York: at 165 West 72nd, William P. Prince, 24, born in N.C., janitor at apartment house, and wife Gertrude P., 30, born in N.C., housekeeper at apartment house.

On 6 June 1912, shortly before he died, Turner Prince made out a will whose provisions included: “I give, devise and bequeath to Ephraim Prince my son & Susie Gray my grandchild the house in which we now live. Ephraim is to have full possession of said house during the minority of said Susie Gray and in return contribute to her support. If at any time he should discontinue to do so, then he shall forfeit ($50.00) Fifty Dollars to my estate, the amount forfeited to be used for the benefit of said Susie Gray. If Susie Gray should die before maturity then said property shall revert to Ephraim in full. Otherwise he is to pay Susie Gray $50.00 upon her becoming of age, and he come in full possession of said property.”

In 1918, Willis Ephraim Prince registered for the World War I draft in Manhattan County, New York. Per his registration card, he was born 22 January 1886; lived at 2470-7th Avenue, New York City; was an unemployed licensed engineer; and his nearest relative was wife Gertrude Prince.

On 22 November 1919, Willis E. Prince, 31, of Edgecombe County, son of Turner and Sarah Prince, married Marina White, 21, of Edgecombe County, daughter of Edgar and Marietta Wilkins, at the courthouse in Wilson.

In the 1920 census of Tarboro, Edgecombe County: on Tarboro Road, carpenter Willis Prince, 32; wife Marina, 21, teacher; and daughter Vivian, 8 months.

On 31 December 1920, Tarboro’s Daily Southerner reported the arrests of four men for stealing a safe from Willis Prince’s store in Tarboro.

On 21 November 1922, Willis Prince, 36, son of Turner and Sarah Prince, married Mary Gear, 36, daughter of Dan and Sarah Gear, in Wilson. A.M.E.Z. minister B.P. Coward performed the ceremony in the presence of Laura Peele, S.A. Coward, and Louise Cooper.

In the 1925 and 1928 Hill’s Wilson, N.C., city directories, Willis and Mary Prince are listed at addresses on Suggs Street.

Mary Prince died 14 November 1928 in Wilson. Per her death certificate, she was 45 years old; was born in Wilson County to Daniel and Sarah Gier; was married to Willis Prince; and was buried in Rountree Cemetery. Alice Woodard was informant.

In the 1930 census of Philadelphia, Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania: at Chestnut Hill Hospital, Willis E. Prince, 49, boarder, porter at public hospital; born in North Carolina.

On 27 January 1934, Willis Prince, 47, son of Turner Prince and Sarah [maiden name not listed], married Alma Mae Hines, 29, daughter of Amos and Sarah Hines, in Wilson. C.E. Artis applied for the license, and A.M.E. Zion minister I. Albert Moore performed the ceremony in the presence of M.W. Hines, C.L. Darden, and A.M. Dupree.

In the 1940 census of Wilson, Wilson County: Willis Prince, 54, carpenter/private contractor, and wife Allie, [blank].

In the 1941 Hill’s Wilson, N.C., city directory: Prince Willis E (c; Ella M; Small Town Club) h 205 Stantonsburg

1941 Wilson, N.C., city directory.

The last will and testament of Willis E. Prince, 1947. Daniel McKeithen, Talmon Hunter, Dr. Kenneth Shade, S.P. Artis, and Daniel Carroll witnessed the document.

Willis Ephraim Prince died 2 October 1950 at Mercy Hospital. Per his death certificate, he was born 17 January 1889 in Edgecombe County to Turner Prince and Sarah [maiden name not listed]; was married to Allie Mae Prince; lived at 205 Stantonsburg Street, Wilson; and worked as a merchant at his own business.

For more about Princeville, see here and here and here.