On 17 March 2021, the Wilson Daily Times printed this photo of Paul Sherrod holding a renewal notice sent in 1911 to his great-grandfather Jack Sherrod by John D. Gold, the newspaper’s founding editor.

See Drew C. Wilson’s article here.

On 17 March 2021, the Wilson Daily Times printed this photo of Paul Sherrod holding a renewal notice sent in 1911 to his great-grandfather Jack Sherrod by John D. Gold, the newspaper’s founding editor.

See Drew C. Wilson’s article here.

Wilson Daily Times, 8 December 1928.

I. Garland Penn, The Afro-American Press and Its Editors (1891).

Samuel N. Hill died in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, in March 1918. The New York Age ran his obituary.

New York Age, 30 March 1918.

Many thanks to John Sullivan of Wilmington’s non-profit Third Person Project for sending this Black Wide-Awake’s way.

Wilson Daily Times, 2 July 1976.

For highlights of the single surviving issue of the Blade, the original of which is housed at Freeman Round House and Museum, see here and here and here and here.

New York Age, 16 September 1922.

I’m looking forward to speaking on the development of Wilson’s African-American neighborhoods tonight at the Wilson County Public Library. The Wilson Times ran this interview Tuesday; I appreciate the hometown love.

On 17 February 1882, the Wilson Advance ran a brief piece announcing that the colored people would begin publishing the Wilson News in March of that year, and S.N. Hill would be an editor of this for-the-people-by-the-people paper. (No editions are known to survive.) Two months later, Samuel Hill was well-enough established in local politics to be appointed a poll holder in Wilson.

Wilson Advance, 14 April 1882.

The Advance was the first foray of notorious, but much celebrated, Josephus Daniels into the newspaper business, and the white supremacist world view he later honed to a fine point at Raleigh’s News & Observer was on naked display in its pages. Local and regional Republican politics, which were dominated by African-Americans, were not spared. That the Advance‘s presses printed Hill’s paper did not shield him either. The Advance printed the satirical letter below (and a similar one a few weeks later) purportedly written by “Jedekiah Judkins” to George W. Stanton, a die-hard Unionist and Republican.

Wilson Advance, 20 October 1882.

Snide commentary in the white press notwithstanding, Hill networked and exchanged ideas with other black journalists and political figures in eastern North Carolina the following summer. [Was the Independent yet another newspaper?]

Wilmington Daily Review, 5 July 1883.

His statewide networking secured his designation as a marshal for the state colored fair.

The Banner-Enterprise (Raleigh), 27 October 1883.

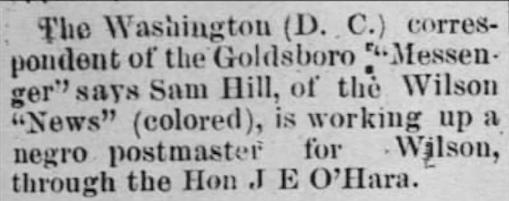

The News apparently was still in publication in December 1883 when the Advance printed a small blurb suggesting that Hill was angling for postmaster appointment under the auspices of James E. O’Hara, who had been elected in 1882 as a Republican to the United States House of Representatives from North Carolina’s “Black Second” district.

Wilson Advance, 21 December 1883.

Months later, however, the paper seems to have faltered, and Hill had to relaunch the publication.

Wilson Advance, 25 April 1884.

On 22 January 1885, the Advance printed a brief note that a Samuel Hill referred to in a recent article as having been chaged with perjury in Toisnot township was not the “Samuel N. Hill that all our people know.” The known Hill had stopped by the Advance‘s offices and informed them that “he is now traveling for a newspaper at New Bern.”

By the late 1880s, Hill was living in Wilmington, where newspaper reports note that he was active in efforts to encourage African-American investment in local railroad companies.

Not quite five years later, the Advance reported that Hill, an “irrepressible” “coon,” had received a patronage position in Washington. There is no evidence that he returned to Wilson.

Wilson Advance, 29 August 1889.

Within the next few years, however, Hill withdrew from active politics and began to espouse an accommodationist philosophy. On 27 November 1898, New Bern Daily Journal published a letter by Hill lashing out at “unscrupulous white Republicans” and “scheming politicians” and praising the good white folks who had always shown “the best sympathy” to colored people. “Make friends with the best white people among whom you live,” he exhorted. “Their interests are greater than yours and the maintenance of happiness depends upon their efforts.” A few weeks later, on 10 December, the Wilmington Morning Star cited Hill’s “sensible and calm utterances” in the wake of the Wilmington Insurrection as a positive contrast to the stridency of Congressman George E. White, a “bumptious strutter.” For his part, Hill had pshawed agitation against “fancied evils which do not exist” and counseled “[t]he best public meeting for the negro to attend is his church, where he may commune with his God, and where he may be influenced for good.”

So where did Sam Hill come from? And where did he go?

Most likely, he was the Samuel Nelson Hill who opened two accounts at the Freedmen’s Bank’s New Bern branch. The first time, on 9 August 1871, Hill was 12 years old. His account registration card notes that he resided in Bragg’s Alley; was light-complected; was the son of Moses M. and Adeline Hill; had brothers named Benjamin Starkey (dead), Moses Hill and Thomas Hancock; and sisters named Carolina and Holland Hill. The boy signed his own name.

Hill opened another account on 8 June 1874. Per that account registration, he was born and “brought up” in New Bern; resided in Windsors Brickyard, Virginia; worked for Dr. Windsor; was 15 years old; was of yellow complexion; and had a brother named Noah Harper, also of New Bern. Samuel signed his name with a mature version of his earlier signature and with a confident, curlicued firmness that connotes deep literacy.

In the 1880 census of New Bern, North Carolina: on Elm Street, shoemaker Moses Hill, 49, wife Adelaine, 43, son Samuel, 20, a shoemaker, and daughter Susan, 1. Moses reported that he suffered from rheumatism and Susan from whooping cough.

Hill probably arrived in Wilson in 1881. His star there burned bright and brief, and by about 1885, he had moved on. His whereabouts the decade of the 1890s are unclear, but just after the turn of the century Hill is found in the Berkshires of western Massachusetts, performing manual labor.

On 19 November 1904, Samuel Nelson Hill, 45, of 288 North Street, Pittsfield, Massachusetts, married Georgeanna Treadwell Vanderburgh, 43, of 6 Cole Avenue, Pittsfield. Hill reported that he was the son of Moses Hill and Adeline Hancock and was born in New Bern, North Carolina. He worked as a laborer, and this was his first marriage.

In the 1910 census of Pittsfield, Berkshire County, Massachusetts: electrical works janitor Samuel N. Hill, 50, and wife Georgeanna, 49.

Samuel Nelson Hill of 164 Linden died 21 March 1918 in Pittsfield, age 58 years, five months, five days.

The Wilson Daily Times is the source of many of the newspaper articles posted at Black Wide-Awake. I am not unmindful of the racist over- and undertones of many of the clippings, especially those reporting alleged criminal activity. Nevertheless, they have value as imperfect documentation of the existence of so many African-Americans whose lives went otherwise unrecorded. Journalist Karl Fleming made his name covering the Civil Rights movement — most notably, Freedom Summer — for Newsweek magazine in the early 1960s. Fleming’s newspaper career began about 1947 at the Daily Times, which, in Son of the Rough South: An Uncivil Memoir (2005), he credits with introducing him to the brutal racist policies of his native state.

Fleming devotes several chapters to his time in Wilson. His behind-the-scenes explanation of the Times‘ race conventions is illuminating:

“The style of the Daily Times decreed that unmarried black women of whatever age be called ‘girl.’ A married ‘colored’ woman after being identified by her whole name, perhaps, perhaps Elsie Smith, in the first mention, would in succeeding graphs be called ‘the Smith woman.’ This avoided the honorifics ‘Miss’ or ‘Mrs.’ being applied to colored women. Colored men, of course, were never referred to as ‘Mr.,’ not even on the full page that ran ever Saturday headlined ‘News of the Colored Community,’ which catalogued the doings of the colored Charles L. Darden [sic] High School, church and Sunday school events, marriages, funerals, and social clubs. Darden ran the colored funeral home and a colored insurance agency and was the colored community’s most substantial citizen.”

His physical description of the town remains recognizable in many ways, even in the water fountains have been dismantled:

“Wilson and the surrounding county was half white and half colored. The town squatted in the sweltering heart of the table-flat and sandy North Carolina coastal plain, throughout which tobacco was the main cash crop. In the center of town, in front of a marble courthouse with six fluted Doric columns, two magnolia trees, and a confederate statue, were ‘White’ and ‘Colored’ water fountains.”

“The old train depot, the faded brick six-story Cherry Hotel alongside it, and the tracks of the Atlantic Coast Line railroad separated these black and white worlds.”

“What the colored people across the tracks may actually have felt about segregation in general and separate schools specifically no one in the white world knew. It was simply assumed that what they said to the white people was true — that they were content with the status quo. The pillars of the black community, the ministers and school teachers and the owners of the few colored businesses allowed to exist because whites wanted nothing to do with them — such as restaurant, beauty parlors, barber shops, funeral homes, pool halls, and juke joints patronized entirely by colored people — did not publicly protest or resist. There seemed to be among them a seeming general air of good-natured acceptance. When one of them excelled, or died, it was said that “he was a credit to his race,” suggesting that ordinary blackness was a debit somehow.”

Fleming exaggerates the uniform decrepitude of East Wilson’s building stock. As this blog has amply demonstrated, East Wilson was a lot more than shotgun rentals in need of whitewash. There were certainly a fair number of those though.

“The colored community was a close-packed warren of gray unpainted shotgun shacks rented from white landlords on dirt alleys across the railroad tracks. Its only paved roads were Nash Street, becoming Highway 41 [91] going east into the country towards the coast, and U.S. 301 going north and south, the principal highway from New York to Miami. Its inhabitants were for the most part menials of every sort, field hands on the surrounding tobacco farms, manual laborers for the city and county maintenance departments, and unskilled workers in the tobacco warehouses and wholesale packing houses.”

And then this observation, followed by a truism:

“Few white people ventured into ‘n*ggertown.’ … The arrival of a white man could mean nothing good. He was either ‘the law,’ a bill collector, or someone selling something — usually life or burial insurance.”

Fleming also offers a reporter’s assessment of (and white Wilson’s take on) the trial of Allen T. Reid, who was sentenced to death in 1949 for burglary.

Wilson Advance, 16 February 1883.

A year after the Wilson News made its debut (and apparently quickly failed}, persons unknown launched the Colored Independent in Wilson. No issues are known to survive.

Wilson Advance, 17 February 1882.

Apparently, this Wilson News was a short-lived venture. Another newspaper by the same name — but pretty clearly not operated in the interests of the colored race — was published in 1899.