From The News and Observer, today’s headline: “Daniels family removes statue of racist ancestor in Raleigh“:

“Frank Daniels Jr. of Raleigh, retired president and publisher of The News & Observer, said in a statement Tuesday that his grandfather’s bigoted beliefs overshadowed his other accomplishments, including, Daniels said, ‘creating one of the nation’s leading newspapers.’”

“’Josephus Daniels’s legacy of service to North Carolina and our country does not transcend his reprehensible stand on race and his active support of racist activities,’ Daniels said. ‘In the 75 years since his death, The N&O and our family have been a progressive voice for equality for all North Carolinians, and we recognize this statue undermines those efforts.’”

… to the unvarnished:

… to the grotesque:

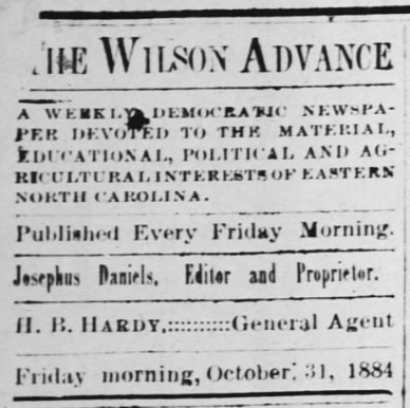

Wilson Advance, 31 October 1884.

The Wilson County Historical Association erected a marker for Josephus Daniels near the county courthouse. It makes no mention of his most efficacious role — spearhead of the disenfranchisement and general subjugation of North Carolina’s African-American citizenry. Despite repeated calls for its removal, notably led by the indefatigable Castonoble Hooks, the marker stands.

I amplify Mr. Hooks’ voice here: TAKE IT DOWN.

——

Update, 18 June 2020: Today, the city of Wilson quietly removed the historical marker honoring Josephus Daniels today and returned it to the Wilson County Historical Association.

“Wilson removed Josephus Daniels marker: Family cited his ‘indefensible positions on race,” Wilson Daily Times, 18 June 2020.