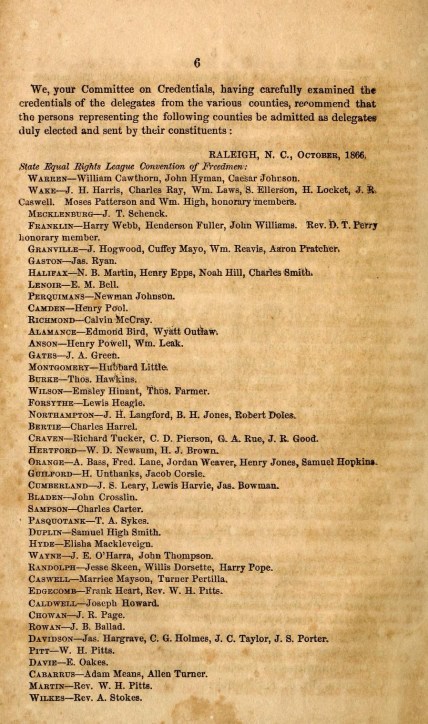

When searching for information about the men and women enslaved by Council Applewhite, I ran across this transcription, which appears to reflect an article published on 8 July 1875 in the Norfolk Virginian:

THE FOLLOWING HISTORY OF GEORGE APPLEWHITE, THE ROBESON COUNTY OUTLAW RECENTLY CAPTURED IN GOLDSBORO IS GIVEN BY THE MESSENGER.

George Applewhite was born in Wilson County and was the slave of Council Applewhite. His half brother, Addison Applewhite, lives in Goldsboro. His mother now lives near Stantonsburg. George was afterwards given in marriage to Mr. William R. Peacock of Wythe and apprenticed to learn the plastering trade. He is a dark mulatto stoutly built about 34 years old. In 1866 he accompanied Mr. Peacock to Robeson where he worked in turpentine. It was there he married a sister of Henderson Oxendine, one of the Lowery Gang who was afterwards hung at Lumberton. Applewhite’s wife now lives in Robeson County being thrown by marriage in association with the outlaws then warring on the citizens of Robeson County he soon became one of the gang and is said to have been a most desperate character. In 1869 he was arrested on charges of being an accomplice in the killing of Sheriff Reuben King for which he was tried and convicted and sentenced to be hanged in Columbus County.

A Wilson County man rode with Henry Berry Lowry?

[NOTE: What follows is an abbreviated account of George Applewhite’s involvement with the Lowry Band. I strongly urge you to seek out a more in-depth understanding of the Lowry War, which was rooted in the increasing marginalization of Native people and free people of color in the antebellum period and fierce conflict arising from conscription of Native men to work for the Confederacy during the Civil War. As an introduction to the themes of resistance, revenge and redistribution of wealth that intertwine in this period, please see North Carolina Museum of History’s Community Class Series: Henry Berry Lowrie, Lumbee Legend, which features, among others, the incomparable Lumbee historian Malinda Maynor Lowery.]

After a series of raids and murders of both Native and white men, on March 3, 1865, Allen Lowry and his son William were put to a sham trial, found guilty of theft, and summarily executed. Their deaths sparked the infamous seven-year Lowry War.

George Applewhite arrived in Robeson County after the War began, and his 1868 marriage to Henry Lowry’s first cousin, Elizabeth Oxendine, presumably drew him into the conflict.

On 23 January 1869, Applewhite allegedly shot and killed former sheriff Reuben King during a robbery attempt. Applewhite and seven others were arrested in the fall of 1869. In April 1870, he and Steve Lowry were tried, convicted, and sentenced to death. They were sent to Wilmington, North Carolina, to a secure jail in which Applewhite’s brother-in-law Henderson Oxendine was being held, but escaped with the help of Henry Lowry’s wife, Rhoda Strong.

In October 1870, after a raid on a neighbor’s still, a posse cornered the gang at Applewhite’s house. Applewhite was injured in the resulting firefight, but escaped into Long Swamp with others. Henderson Oxendine was captured at Applewhite’s house the following February and hanged in March. In April, Applewhite was ambushed outside his house. Though shot in the neck and back, he escaped. (His children told his attackers he had been shot twice in the mouth, but spit both bullets out.) His brother-in-law Forney Oxendine was arrested. Applewhite holed up at Henry Berry Lowry’s cabin, which came under attack on April 26. Applewhite and Lowry escaped the gun battle and spent several weeks raiding before breaking Forney Oxendine out of jail.

Officials arrested Betsy Applewhite and other family members of the Lowry band in an effort to draw the men out into the open. Lowry threatened retaliation against Robeson County white women, promising “the Bloodiest times … that ever was before.” On July 17, the Lowry band ambushed a police guardsman, resulting in several deaths.

Charlotte Democrat, 18 July 1871.

Shaken citizens demanded a release of the Lowry gang’s wives, and a truce of sorts took hold.

Eight months later, in February 1872, the Lowry Band raided Lumberton, escaping with more than $20,000 from private safes. Henry Berry Lowry was never (officially) seen again, creating a mystery that only burnished his legend to cultural icon. Applewhite, too, disappeared.

The long-winded heading of the New York Herald‘s extensive excerpts from correspondent George Alfred Thompson provides a rough summary of the entire saga (at least from the standpoint of white Robeson County), and the detailed map accompanying the article marked George Applewhite’s cabin with the letter B just south of Shoeheel, or modern-day Maxton. M, between his house and the railroad, marks the place he was shot in 1871.

The Swamp Angels. — The Blood Trail of the North Carolina Outlaws. — How Lowery Avenged the Murders of a Father and a Brother. — Cain’s Brand the Test of Admission to the Gang. — A War of Races. — The Outlaws in the Swamp-The Judge on the Bench-The Ku Klux on their Nightly Raids. — Lowery Breaks Prison Twice. — Sheriff King, Norment, Carlisle, Steve Davis and Joe Thompson’s Slave Murdered by the Band. — Killing the Outlaws’ Relatives When They Cannot Catch the Gang. — A Promise That Was Kept: “I Will Kill John Taylor — There’s No Law for Us Mulattoes.” — Aunt Phoebe’s Story. — The Hanging of Henderson Oxendine. — Outlaw Zach McLaughlin Shot By an Impressed Outlaw. — The Black Nemesis.

New York Herald, 8 March 1872.

Applewhite was arrested in Columbus, Georgia, late that fall. The Herald‘s breathless report mentions that he had committed a “terrible murder in the eastern section of the State at the close of the Civil War,” but this appears to be a misattribution. Applewhite was not in Robeson County at that time.

New York Herald, 6 November 1872.

But was this in fact George Applewhite? I have found no follow-up to this pronouncement, and no report of his extradition to North Carolina. Rather, in July 1875 Applewhite was arrested in Goldsboro, where he had been living for years under the pseudonym Bill Jackson. Two African-American men, Bryant Capps and William Freeman, violently apprehended him, and he was jailed in Columbus County, N.C.

Weekly Telegraph and Journal & Messenger (Macon GA), 13 July 1875.

Applewhite obtained top-notch counsel, who exploited a technicality to win his release under state’s Amnesty Act, which pardoned persons found responsible for political violence in the years after the Civil War. The Act had been intended to shield Ku Klux Klansmen from prosecution and contained a provision excepting Steve Lowry, alone of the Lowry Band, from its protection. (The General Assembly likely assumed Henry Lowry and Applewhite were dead.) After a North Carolina Supreme Court ruling on the issue of whether Applewhite’s appeal of his conviction and death sentence had rendered him eligible for amnesty, Applewhite was freed.

Raleigh’s Daily Sentinel published a sympathetic portrait of Applewhite shortly after his release, outlining his background and questioning his culpability in the crimes attributed to him.

Daily Sentinel (Raleigh, N.C.), 28 June 1876.

Applewhite did return to Goldsboro. His wife Betsy and children remained in Robeson County, and he remarried in 1880. His date of death is not known.

——

George Applewhite, “The North Carolina Bandits,” Harper’s Weekly, 30 March 1872, p. 249.

On 10 September 1869, the Wilmington (N.C.) Journal published descriptions of “the Robeson outlaws,” including George Applewhite:

Though Applewhite is described elsewhere as a dark mulatto, Herald correspondent George Alfred Thompson sought to demonize him by resorting to exaggerated stereotypes:

“George Applewhite is a regular negro, of a surly, determined look, with thick features, woolly hair, large protuberances above the eyebrows, big jaws and cheek bones and a black eye.

“He is a picture of a slave at bay. Mrs. [Harriet Beecher] Stowe might have drawn ‘Dred‘ from him.”

And: “Applewhite was an alert, thick-lipped, deep-browed, wooly headed African, with a steadfast, brutal expression.”

This pixelated image of Applewhite, the only version I could find on line, is the only known photograph of the man.

——

George Applewhite was born in the Stantonsburg area of what is now Wilson County about 1848 to Obedience Applewhite and Jerre Applewhite.

George Applewhite married Elizabeth C. Oxendine on 15 August 1868 in Robeson County, North Carolina.

In the 1870 census of Burnt Hall township, Robeson County: Betsey Appelwhite, 28; her children John, 12, Robert, 10, Emilie, 4, and Adeline, 2; and brother Furney Oxendine, 20.

In the 1880 census of Burnt Hall township, Robeson County: Betsy Applewhite, 38, described as a widow; and children Mariah, 15, Addena, 11, Forney, 6, and Polly, 4.

In the 1880 census of Goldsboro, Wayne County, North Carolina: George Applewhite, 32, plasterer, living alone.

On 12 September 1880, George Applewhite, 32, of Wayne County, son of Jerre and Beady Applewhite (father dead; mother living in Wilson County), married Martha Hodges, 16, of Wayne County, daughter of Graham and Mary Hodges, in Goldsboro, Wayne County.

The last reference to George Applewhite I’ve found is this account of Christmas Day fight between Applewhite and Arthur Williams:

Goldsboro Messenger, 31 December 1883.