Wilson Daily Times, 8 October 1912.

——

In the 1900 census of Wilson township, Wilson County: farmer George Braswell, 52; wife Adeline, 47; children Mollie, 22, Mattie, 18, Caroline, 16, Victoria, 13, Melvina, 12, Cora, 10, and Ernest, 9; and grandchildren James, 3, and Frederick, 3 months.

On 24 October 1912, Ernest Braswell, 20, of Wilson, son of W. and Adeline Braswell, married Teenie Sims, 17, of Gardners township, daughter of Caesar and Adeline Sims, at Caesar Sims’ in Gardner’s.

In the 1920 census of Toisnot township, Wilson County: Ernest Braswell, 27; wife Tinie, 22; daughter Lillian, 7; and brother Willie, 21.

On 8 September 1898, Rufus Whitley, 26, of Stantonsburg, son of John and Isabella Whitley, married Mattie Pree, 23, of Wilson, daughter of Ben and Bettie Pree, in Gardners township.

In the 1900 census of Stantonsburg township, Wilson County: farm laborer Rufus Whitley, 25; wife Mattie, 25; daughters Caroline, 7, and Isabella, 3 months; and brother-in-law Wiley Dupree, 19.

In the 1910 census of Saratoga township, Wilson County: Rufus Whitley, 37; wife Mattie, 30; and children Mattie, 8, Wiley, 3, and Rufus B., 3 months.

In the 1920 census of Saratoga township, Wilson County: Rufus Whitley, 49; wife Mattie, 45; and children Wiley, 13, Benjamin, 12, Bettie, 7, and Lizzie, 11 months.

In the 1930 census of Saratoga township, Wilson County: Rufus Whitley, 59; wife Mattie, 52; and children Ben, 20, Bettie A., 18, Lizzie J., 11, and Matta B., 6; and lodger Jesse King, 22.

- “the King boys,” Tart, Otto, Jack, Marcellus, Sylvester and Lum

In the 1880 census of Stantonsburg township, Wilson County: farm laborer Shandy King, 24; wife Nancy, 23; and sons Zadock, 3, and Jackson, 1.

In the 1900 census of Stantonsburg township, Wilson County: farmer Shandy King, 51; wife Nancy, 49; and children Marcellus, 19, Shandy, 16, Mahala, 14, Columbus, 12, Sylvester, 10, Otto, 7, and Harriett, 6.

In 1917, Sylvester King registered for the World War I draft in Wilson County. Per his registration card, he was born in March 1891 in Wilson County, N.C.; farmed for W.F. Woodard; and was single.

In 1917, Columbus King registered for the World War I draft in Wilson County. Per his registration card, he was born 13 July 1890 in Wilson County; lived in Stantonsburg; was single; and was a farm laborer for W.T. Harrison. He was short and stout, with brown eyes and black hair.

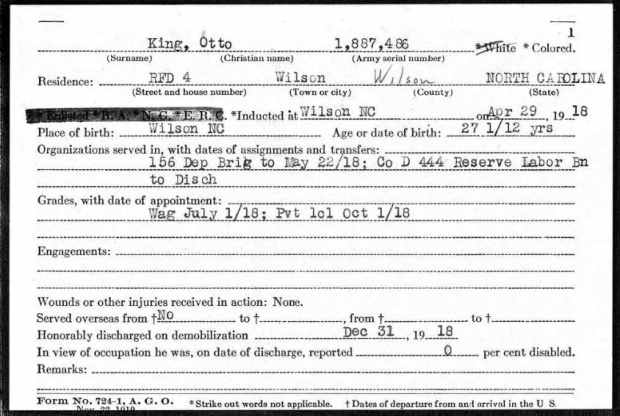

In 1918, Otto King registered for the World War I draft in Wilson County. Per his registration card, he was born in 22 March 1891 in Wilson County, N.C.; farmed for Charley Walston; and was single.

On 2 February 1922, Sylvester King, 28, of Wilson, son of Shandy and Nancy King, married Etta Mitchell, 23, of Wilson, daughter of Jim and Martha Fields, in Wilson. Disciples minister J.W. Pitt performed the ceremony in the presence of Wesley Bullock, Walter Bullock, and Tom Jones.

Sylvester King died 26 June 1930 at Mercy Hospital, Wilson. Per his death certificate, he was born in 1890 in Wilson County to Shandie King and Nancy Anderson; was single; and worked as a tenant farmer for Chester Jordan. He was buried in Wilson. Informant was York King.