The People’s Voice (New York, New York), 9 March 1946.

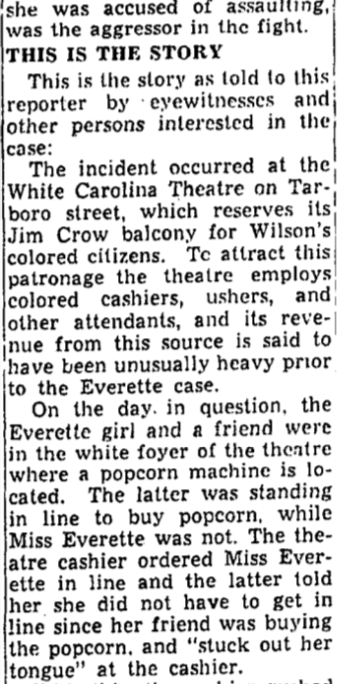

With Marie Everett battling imprisonment, Julia Armstrong went North for help. Direct from New York City’s Penn Station, she headed to the office of The People’s Voice, the Harlem newspaper founded in 1942 by Adam Clayton Powell Jr. She gave a literal blow-by-blow of the events at the Carolina Theatre and pled for funds to assist Everett. For her own part, Armstrong said she planned to sell her “tourist home” and move North after Everett was released. (Wilson, of course, is not “a few” miles from Tennessee.)

——

In the 1940 census of Wilson, Wilson County: at 411 East Green, Hallie Armstrong, 48, pool room operator; wife Julia, 29; and lodgers Annie M. Brown, 39, of Mooresville, Iredell County, hospital nurse; Jeanett M. Lee, 24, of Mount Olive, Wayne County, hospital nurse; and Lawrence Peacock, 27, of High Point, sewer project laborer.

Hallie Armstrong died 18 June 1947 at his home in Farmville, Pitt County, N.C. Per his death certificate, he was 55 years old; was born in Halifax County, N.C., to John Armstrong and Marina Lark; was married to Julia Armstrong; operated a show repair shop; and was buried in Rest Haven Cemetery, Wilson.

However, in 1950, she was still in Wilson: in the 1950 census of Wilson, Wilson County: at 411 East Green, widow Julia Armstrong, 39, born in Kentucky, and lodgers Mary Rose, 29; Anne Everette, 2; Herbert Rose Jr., born in July; Edward Harris, 20, construction company bricklayer; McDonald Hayes, 33, electric power company laborer; Josephine Hayes, 28, cotton picker on farm; and Willie Mack Hayes, 15, cotton picker on farm.

Julia Miller Armstrong died 9 March 1964 in Jacksonville, Onslow County, N.C. Per her death certificate, she was born 14 September 1904 in south Carolina to John F. Miller and Bessie Scruggs; she did domestic work as a cook; and she was buried in Rest Haven Cemetery, Wilson.