As my father put it, all the “big dogs” lived on Green Street. The 600 block, which ran between Pender and Elba Streets, two blocks east of the railroad that cleaved town, was home to much of Wilson’s tiny African-American elite. There, real estate developers, clergymen, doctors, undertakers, educators, businessmen, and craftsmen built solid, two-story Queen Annes that loomed over the surrounding neighborhood. Here were early 20th-century East Wilson’s movers and shakers; Booker T. Washington slept here.

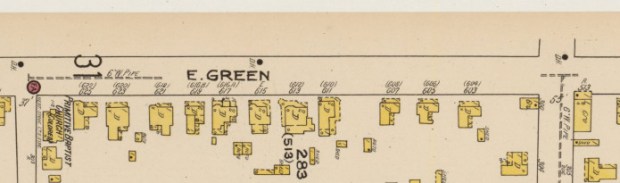

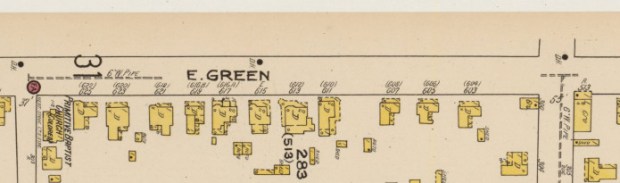

The north side of Green Street as depicted in a 1922 Sanborn map.

By my childhood, however, a half-century into its reign, Green Street had slipped. Wilson’s small but growing black middle class was building ranch houses further west, and Green was home to, if not working class renters, then dowagers struggling to stay on top of the maintenance costs imposed by multi-gabled roofs; oversized single-paned windows; and wooden everything. Still, Green Street’s historical aura yet shimmered, and a drive down the block elicited pride and wonder.

In 1988, East Wilson, with Green Street its jewel, was nominated for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places. Every house on the block depicted above was characterized as “contributing,” and the inventory list contained brief descriptions of the dwellings and their owners. Historic status, though, could not keep the wolves from the door. Even as the city’s Historic Properties Commission was wrapping up its work, East Wilson was emerging as an early victim of that defining scourge of the late 1980s — rock cocaine. As vulnerable old residents died off — or were whisked to safer quarters — crackheads and dealers sought refuge and concealment in the empty husks that remained. Squatters soiled their interiors and pried siding from the exteriors to feed their fires. One went ablaze, and then another, and repair and reclamation seemed fruitless undertakings.

This is the north side of Green Street now. Facing east toward Carroll Street, the left edge of the frame is just west of #605. There is not another house until you get to #623. They are gone. The homes of Hardy Tate and C.E. Artis, of the Hines brothers, of Dr. Barnes, of Charlie Thomas, of Rev. Davis. Abandoned. Taken over. Burned up. Torn down. Gone.

These four houses (##603, 605, 623 and 625) and a church at the corner of Elba are all that remain of the buildings shown in the 1922 Sanborn map above.

Photograph taken by Lisa Y. Henderson, October 2013.