COLORED PEOPLE INDIGNANT.

Eleven Colored Teachers Resign from the Colored Graded School Alleging Discourteous Treatment on the part of Principal Reid and that Mr. Coon Slapped One of Them.

This afternoon a delegation of colored teachers from the Wilson colored school, six in number of eleven that have resigned with Rev. Weeks, pastor of the Tabernacle Baptist Church, colored, and Rev. H.B. Taylor, pastor of the Presbyterian church colored, with a petition addressed to the Board of Education of Wilson County and setting forth therein the reasons for their resignations as teachers from the school.

It seems that the trouble originated when Mr. Coon slapped one of the teachers as she alleged in the face when she was called into his room at the instance of Reid to be reprimanded for a disagreement regarding the opening of the school on Easter Monday, April the first, when the new daylight law went effect.

The teacher alleges that on that particular morning the teachers endeavored to open school on the new time and Principal Reid was late.

When the janitor called him he answered let the teachers and the children wait. School was opened on the old time, and this teacher alleges that she dismissed her pupils when they finished their work at the regular hour at 2:25. She further says that Reid asked her whether she was dismissing school on the old time or the new time and she replied: “I am dismissing on the new time, since these children have been here since 7:30 in the morning.”

She alleges that Reid replied that is your fault, and preferred charges against her to Mr. Coon, and Mr. Coon sent for her to come to his office in the Fidelity building at five o’clock which she did. She alleges the slapping took place then.

The resolutions follow:

Wilson, N.C., April 9, 1918.

To the Board of Education of Wilson County, Superintendent of Schools of Wilson County, and Principal of the Colored Graded School of Wilson; and to All Whom It May Concern:

On account of the discourteous treatment of Prof. J.D. Reid, the principal of the Wilson Colored Graded School, to us as teachers under his direction, and on account of the terrible ordeal through which one of us, a teacher in the above stated school had to go on account of the unchristian and unmanly procedure of the principal, J.D. Reid; which aforestated ordeal if told would cause every man who respects pure womanhood to look upon the above-stated principle, J.D. Reid, as the worst specimen of manhood possible to find.

And further on account of the incompetency and untruthfulness of the above mentioned principal, J.D. Reid, which we are prepared to prove, and which he attempts to hide from the superintendent, Board of Education, and the public in general by a high handed, ironclad and abusive rule over those who serve under him;

We, the undersigned teachers of the Wilson Colored Graded School who have tried in every way to help him, but in return have only been treated as a chain-gang crew under criminal offense, have lost respect for the above mentioned principal, J.D. Reid, and tender our resignation.

Done at the Wilson Colored Graded School, this 9th day of April, 1918.

Miss M.C. Euell, Miss J.B Pride, Miss M.L. Garrett, Miss S.R. Battle, Miss G.M. Battle, Miss G.M. Burks, Miss L.B. Davis, Miss M.M. Jennings, Miss S.D. Wiseman

Since that time two other teachers who live here in town have sent in their resignations, namely: Mrs. Walter Hines and Miss Elba Vick.

Both the Colored Ministerial Union and the Negro Business League have appointed a special committee to take up the matter with the graded school board.

Committee from the Ministerial Union: Revs. H.B. Taylor, president; A. Bynum, Chas. T. Jones, Robert N. Perry and A.L.E. Weeks.

Committee from the Business League: S.H. Vick, chairman; B.R. Winstead, Walter S. Hines, Rev. H.B. Taylor, and Robert N. Perry.

The committee of the Ministerial Union communicated with the Graded School Board on yesterday and is expecting a reply in the very near future. — Wilson Daily Times, 11 Apr 1918.

——

The Board’s reply – that Charles L. Coon and J.D. Reid were blameless – was not surprising. The response of Wilson’s black community, however, was. Following their teachers, parents pulled their children out of the public graded school and established a private alternative in a building owned by S.H. Vick. Financed with 25¢ a week tuition payments and elaborate student musical performances, the Independent School operated for nearly ten years.

THE ACTORS

- J.D. Reid — Judge James Daniel Reid (1872-) was the son of Washington and Penninah Reid.

- M.C. Euell — Mary C. Euell was not a native of Wilson County and, not surprisingly, apparently did not remain in the city long after this incident. I am continuing to search for more about her. — LYH

- J.B. Pride

- M.L. Garrett

- S.R. Battle — Sallie Roberta Battle Johnson (1884-1958) was a daughter of Parker and Ella Battle. She later worked as business manager of Mercy Hospital.

- G.M. Battle — Glace (or Grace) Battle (circa 1890-1972) was another daughter of Parker and Ella Battle. She later married Timothy Black.

- Georgia M. Burke

- L.B. Davis

- M.M. Jennings — Virginia-born teacher Mary Jennings, 28, boarded with the family of Hardy Tate at 208 Pender at the time of the 1920 census.

- S.D. Wiseman

- Mrs. Walter Hines — Sarah Elizabeth Dortch (1879-1967) married Walter S. Hines (1879-1941) in 1907 in Boston, Massachusetts. Born in Goldsboro, Wayne County, she was the daughter of Ralph Whitmore Dortch and Mary Burnett Dortch.

- Elba Vick — Elba Vick, born 1893, was a daughter of Samuel and Annie Washington Vick. She married Carlos C. Valle in Wilson on 12 June 1922. (And also in Rocky Mount, Edgecombe County, on 20 December 1921. Carlos was reportedly living in Durham County, and his parents Celedonio and Leticia Valle lived in New York.) In the 1930 census of Memphis, Shelby County, Tennessee: Puerto Rico-born lodge secretary Carlos C. Valle, 37, wife Elba, 33, and children Melba G., 6, and Carlos Jr., 4.

- Halley B. Taylor

- A. Bynum

- Charles T. Jones — Barber and minister, Rev. Charles Thomas Jones was born in Hertford County in 1878 to Henry and Susan Copeland Jones. In the 1920 census of Wilson, Wilson County, at 667 Nash Street: minister Charlie Jones, 41; wife Gertrude, 39; children Ruth, 61, Charlie, Jr., 14, Elwood, 12, Louise, 10, and Sudie, 4; and mother-in-law Louisa Johnson, 65. He died in Wilson in 1963.

- Robert N. Perry — Rev. Robert Nathaniel Perry was a priest at Saint Mark’s Episcopal Church.

- A.L.E. Weeks

- Samuel H. Vick

- B.R. Winstead — A teacher turned barber, Braswell R. Winstead (circa 1860-1926) was the son of Riley Robins and Malissa Winstead of Wilson County. In the 1920 census of Wilson, Wilson County: Braswell Winstead, 60, wife Ada E., and daughter Ethel L., 13, at 300 Pender Street.

- Walter S. Hines

- Mary Robertson

- Celia Norwood — Celia Anna Norwood (1879-1944), daughter of Edward Hill and Henrietta Cherry, was a native of Washington, North Carolina. She died in Wilson.

- Olivia Peacock — Born about 1895, Olivia Peacock was the daughter of Levi H. and Hannah Peacock. She later married Eugene Norman.

- Sophia Dawson — Born about 1890 to Alexander D. and Lucy Hill Dawson, Sophia Dawson married Wayne County native Jesse Artis, son of Jesse and Lucinda Hobbs Artis.

- Delzell Whitted — Helen Delzelle Beckwith Whitted (1888-1976) was the wife of Walter C. Whitted.

- Lavinia Woodard — Lavinia Ethel Grey Woodard (1891-1921) was the daughter of Ruffin and Lucy Simms Woodard.

- Eva Speight — Eva Janet Speight (1899-1944), native of Greene County, later married David H. Coley.

- Hattie Jackson

- Rose Butler

- Clarissa Williams

- Mrs. J.D. Reid — J.D. Reid married Eleanor P. Frederick on 17 October 1899 in Warsaw, Duplin County, North Carolina. By 1925, despite the disapproval of the community, she was principal of the Wilson Colored Graded School, later known as the Sallie Barbour School.

THE COVERAGE

The shocking stance taken by Wilson’s black community reverberated throughout eastern North Carolina, compelling the principal of a colored graded school in Greenville to intervene. He was quickly pulled up short though, and the Wilmington Dispatch crowed over his discomfiture.

Wilmington Dispatch, 23 April 1918.

This was a serious matter indeed; Mary Euell pressed charges. On 30 April, 1918, the Wilson Daily Times printed an account of Charles L. Coon’s initial court appearance that was surprisingly detailed and sympathetic toward Euell. (A posture possibly motivated by Coon’s dismissive alleged comments about its editor, Gold.) In summary, Euell and her lawyer arrived before the magistrate only to find that Coon had come and gone, having obtained an earlier court date of which Euell was not notified. Euell’s counsel (who was he?) was granted permission to make an astonishing statement in which he declared that Euell was prosecuting Coon in order to make sure that the public was made aware of what had happened, to assert her rights to protection under the laws of the State of North Carolina, and because rumors were flying that she was a troublemaker who, among other things, had protested against riding in the “colored section” of a train.

Euell then made a statement to the press summarizing the facts of her encounter with Coon and Reid. In a nutshell: Reid called her a liar; she protested; Coon shouted, “Shut up, or I’ll slap you down;” Euell stood her ground and chastised Reid; Coon delivered a blow.

Wilson Daily Times, 30 April 1918.

Wilson Daily Times, 30 April 1918.

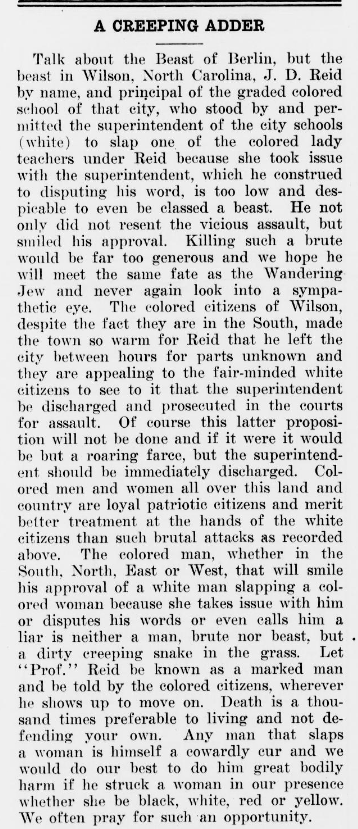

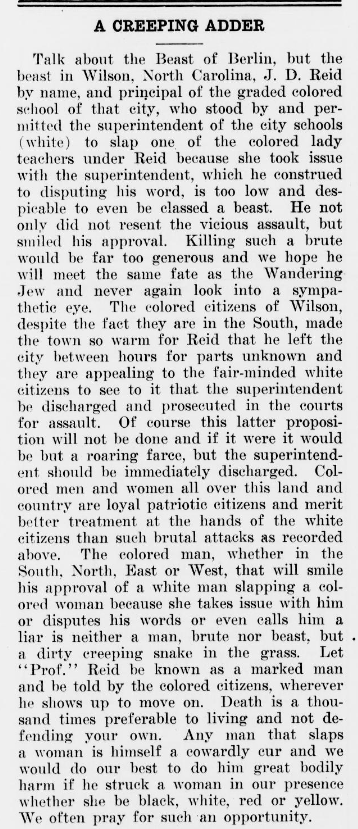

Within weeks, the story had spread from coast to coast. Cayton’s Weekly, published in Seattle, Washington (“[In the interest of equal rights and equal justice to all me for ‘all men up.’ A publication of general information, but in the main voicing the opinions of the Colored Citizens.”) printed this startling editorial:

Cayton’s Weekly, 4 May 1918.

The New York Age got wind of matters a week later, reporting excitedly that Reid had been hounded out of Wilson for his role in the affair:

New York Age, 11 May 1918.

Belatedly, the Age also published a brief bit about the warrant for Coon’s arrest, including a quotation from Coon himself:

New York Age, 18 May 1918.

Ultimately, Coon plead guilty to simple assault and was fined one penny, plus costs. Despite the mass resignation and boycott in April by teachers, students and the black community at large, he and the Wilson public school administration soldiered on. In September, they announced a new staff for the colored graded school and appointed Clarissa Williams principal in J.D. Reid’s stead.

Wilson Daily Times, 24 September 1918.

The New York Age came back with stronger reporting to cover the opening of the Industrial, or Independent, School, as it was called. Hattie Henderson Ricks, who was 7 years old in the spring of 1918, recalled: “First of the year I went to school, and [then] I didn’t go back no more to the Graded School. They opened the Wilson Training School on Vance Street, with that old long stairway up that old building down there — well, I went over there.”

New York Age, 23 November 1918.

Two months later came a progress report on the “school started to protect womanhood” and a request for support:

New York Age, 18 January 1919.

A year after Coon’s slap, the Age continued to report on the courageous stand taken by Wilson’s African-American community, noting that a fundraiser had exceeded its goals, and the school was “flourishing.”

New York Age, 15 April 1919.

Postcard image of Wilson Colored Graded School, J. Robert Boykin III, Historic Wilson in Vintage Postcards (2003).

Oral interview of Hattie H. Ricks by Lisa Y. Henderson; all rights reserved.