I have received the city’s response to my request for documents related to the removal and destruction of headstones from Vick cemetery, made under North Carolina’s Public Records Law.

My initial request to the Wilson Cemetery Commission was made 6 September 2019. (Thanks again to Heather Goff for her quick response.)

I followed up with letters to several city officials in October and November. The city clerk responded quickly to my first letter, providing copies of relevant city council minutes from 1990 to 1995. The city manager and city engineer did not respond at all, even to acknowledge receipt of my request.

On 30 December 2019, I sent a letter to the mayor of Wilson, the city manager, and all seven council members setting forth my concerns and my unanswered requests for information about Rountree, Odd Fellows and Vick cemeteries. At the behest of the city’s new mayor, Carlton Stevens, and council, city attorney James Cauley assumed responsibility for the search for responsive documents. I commend Mr. Cauley for his periodic updates on the status of the city’s response and for his candor concerning the paucity of records.

Here, in their entirety, are the documents I received.

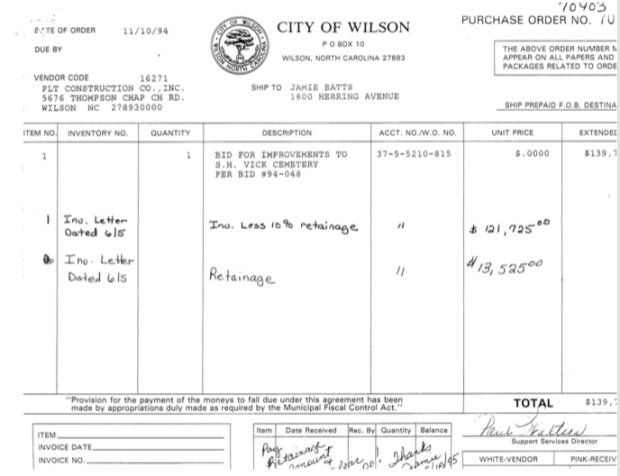

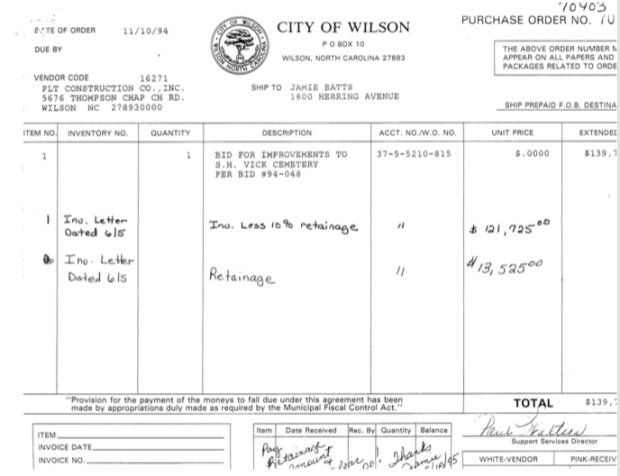

(1) Purchase Order, dated 10 November 1994, for services by vendor PLT Construction, described in “Bid for improvements to S.H. Vick Cemetery.” The document’s right edge is cut off, but the amount the city paid was more than $139,000.

(2) A request for payment of balance due submitted by PLT Construction to the City of Wilson on 5 June 1995. Note the change item: “deduct for replacing headstones and portion of survey work.” PLT did not perform this work and thus credited the city $4500.

(3) A 21 June 1995 invoice for the amount set forth in PLT’s letter above.

(4) Page 1 of a project description entitled “Restoration and Improvement S.H. Vick Cemetery Lane St. Wilson, N.C.” Section 4A of this document is particularly interesting: “All existing graves whether marked by a grave marker or not shall be identified and located so as to be able to be re-located after completion of the work. A detailed survey may be needed in order to ensure that graves are marked in the correct location after completion of the work. A drawing showing all graves shall be prepared for future reference. All existing tombstones shall be removed, labeled, and stored until after all work is completed.” As we know, the grave markers were not relocated to the cemetery. They were stored for an indeterminate period of time, then destroyed.

(5) Page 2 of a project description entitled “Restoration and Improvement S.H. Vick Cemetery Lane St. Wilson, N.C.” See particularly, Section E: “All graves identified and located prior to construction shall be re-located and marked. Graves shall be marked in one of two ways: (1) Tombstones removed from graves prior to construction shall be reset at the proper grave locations. (2) Any unmarked graves which were located shall be marked by means of a small metal marker as typically used in cemeteries. A map showing the locations of all graves shall be furnished to the City of Wilson.”

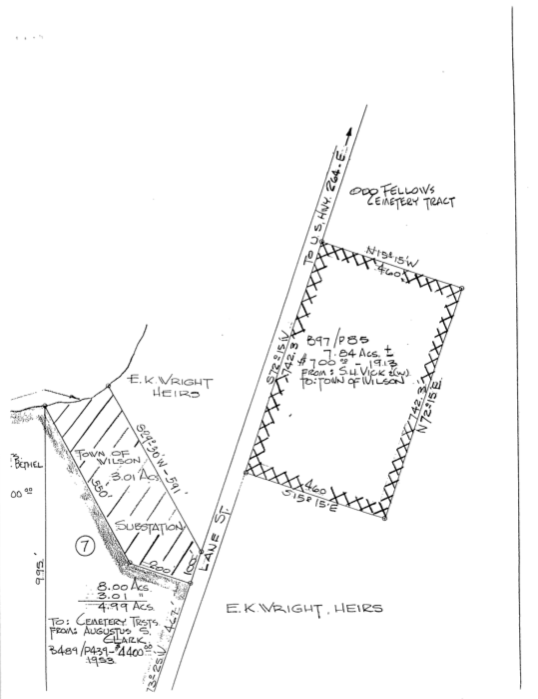

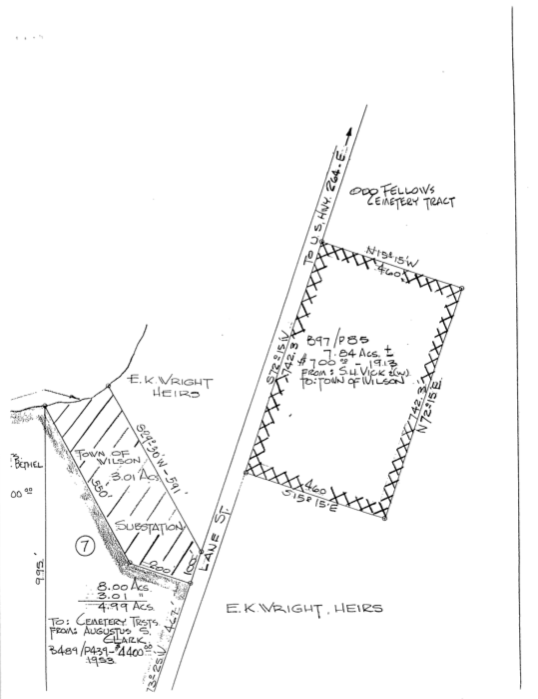

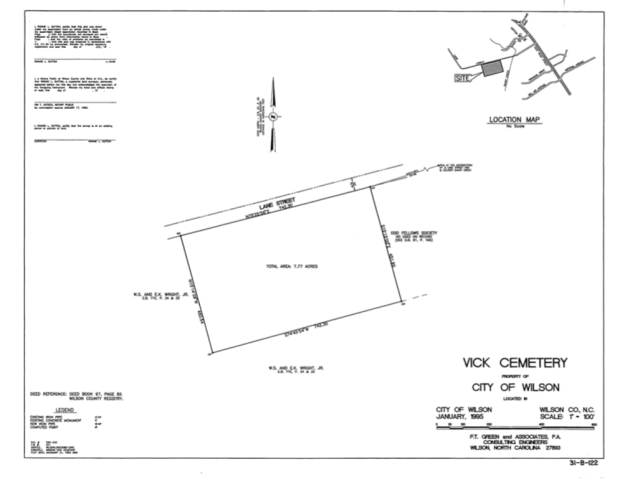

(6) A plat map of the cemetery and surrounding properties, including Odd Fellows cemetery.

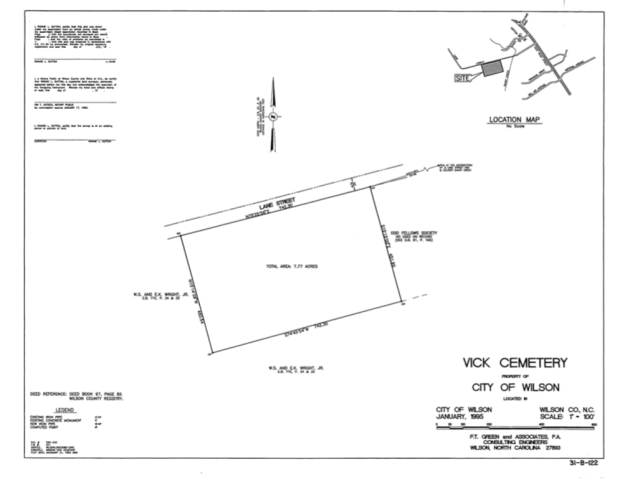

(7) Another plat map prepared by F.T. Green and Associates [now Green Engineering]. Under the label “Odd Fellows Cemetery” is this note: “No deed on record. See D.B. 81, p. 196.”

(8) This map, also prepared by F.T. Green, reveals with terrible clarity the reality of the smooth field that is now Vick cemetery. This map shows the location of every grave found on the site. You have to imagine the boundaries: Lane Street the top, woods to the right (concealing Odd Fellows cemetery) and bottom. The clear strip bisecting the map likely indicates an access lane. Contrary to claims made by public officials in the 1990s, Vick cemetery was laid out quite regularly. Graves were oriented parallel to the road (roughly northeast to southwest) in rows running perpendicular.

Please look more closely. The resolution is awful, but these — hundreds, thousands of? — little marks are not just marks. They are numbers. Each grave was numbered as it surveyed, and the city cannot locate its copy of the key to these numbers. Nor, apparently, can Green Engineering.

The takeaway: the city (or its contractors) surveyed and assigned each grave a number; prepared a map of those graves; removed the gravestones; graded the site; stored, then destroyed the gravestones; and lost the key that identified any of the graves that could be identified.

I need to sit with this for a minute to process my sadness and anger and profound disappointment in the city’s handling of the “restoration and improvement” of a public cemetery founded during the darkest days of segregation and neglected through and after its fifty years as an active burial ground. The graves of the thousands of African-Americans buried in Vick cemetery remain in situ, the names of their dead lost.

Vick Cemetery, Christmas Eve 2019.