I have been unable to find more to elucidate this strange kidnapping story. The Daily Times‘ initial report, which focused more on a novelty angle than on the tragedy, misidentified the baby as “11 months old Mildred Pace,” and suggested that her birth mother had taken her from a black doctor in Washington, D.C., to whom she had sold the child for fifty dollars.

Wilson Daily Times, 14 November 1940.

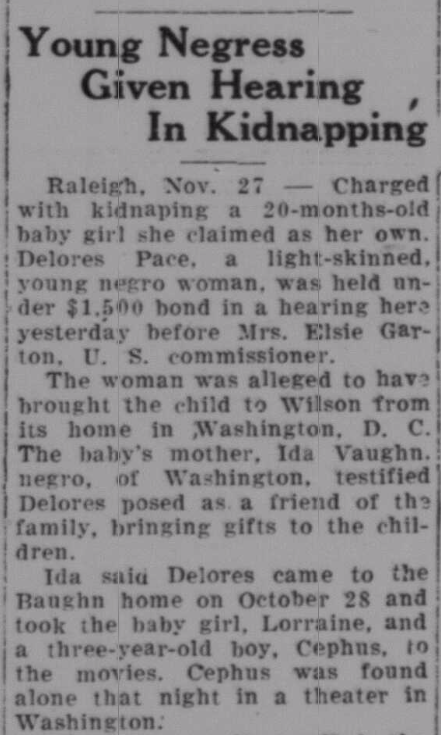

Two weeks later, while still strangely stuck on peripheral details like the light skin color of the baby and her mother, the Times had more details. The child Lorraine was 20 months’ old, and Delores Pace was accused of stealing her from her birth parents, Ida and Massie Vaughn. (Massie Vaughn was a W.P.A. worker, not a doctor.) As best I can decipher, the allegations were these:

Delores Pace befriended the Vaughns under the alias Annie Mae Johnson. On October 28, she took the youngest two of their six children to the movies, where three year-old Cephus was found alone that night. Pace’s friends told police she had taken Lorraine to Wilson. United States marshals were called in to track down Pace and the toddler, and a D.C. policeman followed, took the child into custody and stashed her in the Raleigh City Jail under the care of a janitor.

Pace did not testify at her arraignment. The Vaughns identified their daughter and produced her birth certificate (and the newspaper made much of the contrasting skin tones of all involved.) Pace was ordered to stand trial. After the hearing, Pace told someone (the reporter?) that the child had been born in New York and that her father, Marvin Knight, had promised to marry Pace if Pace showed him the child, and Knight confirmed his paternity. That’s it.

Wilson Daily Times, 29 November 1940.

The 1940 census of Washington, D.C., shows that Lorraine was the youngest of the Vaughns’ six children.

I have not found any record of Delores Pace anywhere.

In the 1940 census of Wilson, Wilson County: on Lodge Street, retail grocer James Henry Knight, 53; wife Ada Elsie, 52; and children Marvin, 22, retail grocery clerk; Evelyn, 19, Nancy Doris, 10, and Joseph Frank, 8. On 6 June 1944, Marvin Robert Knight, 26, of Wilson, son of James and Ada Knight, married Jewell Dean Stokes, of Middlesex, daughter of T.O. and Anna Stokes, in Wake County.