For hundreds of years, the Akan of Ghana and Ivory Coast have used symbols, called adinkra, as visual representations of concepts and aphorisms. Sankofa is often illustrated as a bird looking over its back. Sankofa means, literally, “go back and get it.” Black Wide Awake exists to do just that.

I had never heard of Marie Everett until I read Charles W. McKinney’s excellent Greater Freedom: The Evolution of the Civil Rights Struggle in Wilson, North Carolina. I’m not sure how it is possible that her struggle was so quickly forgotten in Wilson. However, it is never too late to reclaim one’s history. To go back and get it. So, here is the story of the fight for justice for Everett — a small victory that sent a big message to Wilson’s black community and likely a shudder of premonition through its white one:

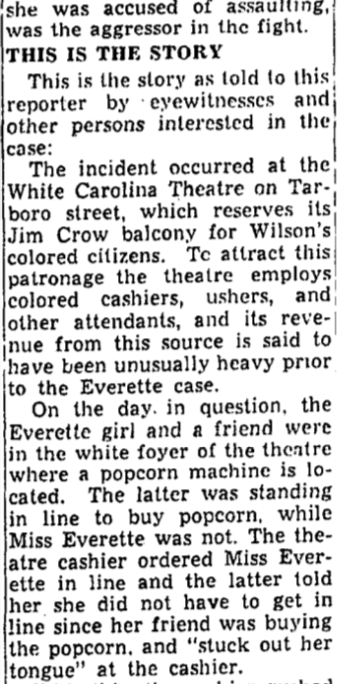

On 6 October 1945, 15 year-old Marie Everett took in a movie at the Carolina Theatre in downtown Wilson. (The Carolina admitted black patrons to its balcony.) As Everett stood with friend Julia Armstrong at the concession stand, a cashier yelled at her to get in line. Everett responded that she was not in line and, on the way back to her seat, stuck out her tongue. According to a witness, the cashier grabbed Everett, slapped her, and began to choke her. Everett fought back. Somebody called the police, and Everett was arrested and charged with disorderly conduct. The next day in court, Everett’s charge was upgraded to simple assault. Though this misdemeanor carried a maximum thirty-day sentence and fifty-dollar fine, finding her guilty, the judge upped Everett’s time to three months in county jail. As Wilson’s black elite fretted and dragged their feet, the town’s tiny NAACP chapter swung into action, securing a white lawyer from nearby Tarboro and notifying the national office. In the meantime, Everett was remanded to jail to await a hearing on her appeal. There she sat for four months (though her original sentence had expired) until a court date. Wilson County appointed two attorneys to the prosecution, and one opened with a statement to the jury that the case would “show the n*ggers that the war is over.” Everett was convicted anew, and Judge C.W. Harris, astonishingly, increased her sentence from three to six months, to be served — even more astonishingly — at the women’s prison in Raleigh. (In other words, hard time.) Everett was a minor, though, and the prison refused to admit her. Branch secretary Argie Evans Allen of the Wilson NAACP jumped in again to send word to Thurgood Marshall, head of the organization’s Legal Defense and Educational Fund. Marshall engaged M. Hugh Thompson, a black lawyer in Durham, who alerted state officials to the shenanigans playing out in Wilson. After intervention by the State Commissioner of Paroles and Governor R. Gregg Cherry, Everett walked out of jail on March 18. She had missed nearly five months of her freshman year of high school.

The Wilson Daily Times, as was its wont, gave Everett’s story short-shrift. However, the Norfolk Journal & Guide, an African-American newspaper serving Tidewater Virginia, stood in the gap. (Contrary to the article’s speculation, there was already a NAACP branch on the ground in Wilson, and it should have been credited with taking bold action to free Everett.)

Norfolk Journal & Guide, 23 March 1946.

Sankofa bird, brass goldweight, 19th century, British Museum.org. For more about the Carolina Theatre, including blueprints showing its separate entrance and ticket booth for African-Americans, see here.

Thank you for sharing this and for being a sankofa.